From the moment we arrived in Chengdu we could see that China would present some challenges. Not the kind of challenges we’re used to: a whole different set of mostly first world problems. Namely, having to rely on our phones for every aspect of life, and mass tourism leading to crowds of people everywhere we went.

I have about zero patience with technology so every time an app which our lives depended on failed us for some mysterious reason – which happened a lot – I longed for the good old days of paying with cash on the spot. Or just showing up somewhere and seeing what happens. I’d rather wing it than have to advance book an appointment just to, say, enter Tiananmen square.

It felt weird to be in cities so modern, so sleek, so similar to home, and yet so very foreign. Everything looked familiar but we were often lost, especially in huge train stations. Translation apps never make for sparkling conversation anyway, and this is how most of our interactions went, most of the time we were in China:

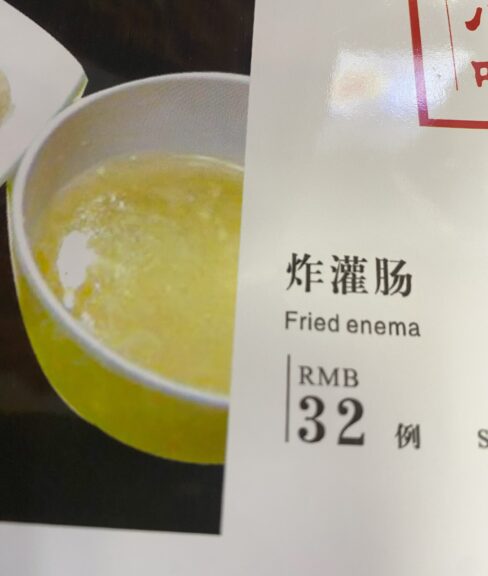

Sometimes we’d see English signs and get our hopes up, but it rarely worked out well:

Oyv (holding out his phone to a smiling girl under an English ‘Information’ sign): ‘Where is platform 62?’

Smiling girl (under the English sign, on her phone): ‘This is not the train station, international friends.’

Oyv (typing frantically as the train is due to depart in five minutes): ‘Ok…where is the train station?’

Smiling girl (points to a distant gate beyond yet another security barrier): ‘Just take this badger.’

China is second only to India in terms of population, but the crowds in India somehow paled in comparison to those we encountered in China. The Chinese are voraciously discovering their own country, which means that everywhere we went we moved in throngs of local tourists, who dutifully trooped around in herds behind tour guides waving flags on sticks.

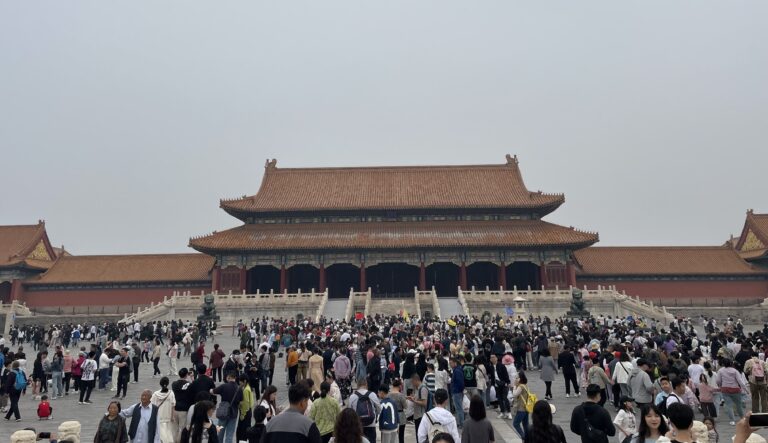

We went to see the Forbidden City in Beijing. It was just us, the Chairman, and about forty thousand tourists:

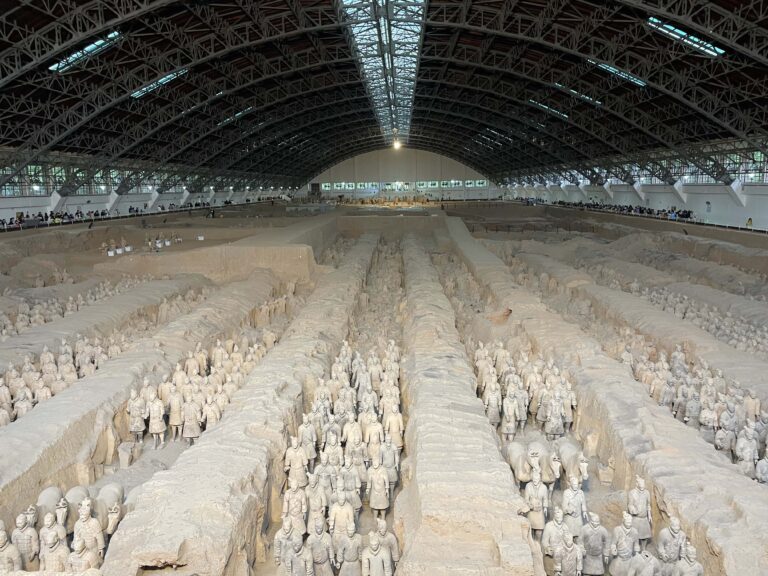

There seemed to be at least three or four tourists for each one of the eight thousand terracotta warriors in Xi’an. The soldiers rested in peace in an Emperor’s grave from 209 BC until 1974 when they were accidentally unearthed by some farmers. Now they’re one of the world’s most famous archaeological discoveries.

At the Panda Base research centre in Chengdu tourists pushed their way to the railings for selfies with a dozing panda’s fluffy butt, and vigilant security guards shouted continuously at lingerers (us) to funnel everybody through the panda nurseries as efficiently as possible.

But we were lucky with the Great Wall and ended up there on a day with surprisingly low numbers. We walked on the wall for hours, marveling not just at the wall itself – but at the green hills rolling away in all directions, devoid of people or buildings.

In the midst of all that, we quickly discovered that it’s always snack time in China (unless it’s time for lunch, or dinner). Translation apps are generally almost useless when it comes to menus anyway:

We gleefully abandoned our phones and just picked, pointed, guessed, and sampled our way through every meal.

Although we generally avoided anything of the foot or beak (or face) variety.

Particularly in Sichuan the food is often insanely hot, and almost always delicious. To combine heat and flavour, we’d opt for hot pot. Pick your sticks, fire up the tabletop stove, bring the pot right under your nose to a lively boil, and get cooking.

Plus, let me just say: Peking duck. I don’t even like to think about how many ducks died to bring us this deliciousness.

Still, after about twelve days in China we were maxed out on apps, crowds, and to a certain extent on duck.

Meanwhile, in Mongolia

Maybe it’s just me, but the very first word that comes to mind when I think of Mongolia is ‘hordes’. To be fair, I haven’t thought of Mongolia often…but for a place once famously home to all sorts of hordes, it’s actually pretty freaking empty now. Landlocked and wedged between Russia and China, today Mongolia is the least densely populated country on earth.

Right next door, and yet so drastically different. What better antidote to big crowds than a roadtrip in an almost-uninhabited country? The Gobi desert, the endless steppe, the taiga – all that vast emptiness where our phones wouldn’t work reliably anyway. It was just waiting to be explored. And as it turned out, my phone got stolen within a day of arriving in the capital, which solved the problem of device-dependency for me.

To reach this mysterious land, we first spent a sleepless night on a bus from Beijing to the Mongolian border. Since we never quite understood what was happening in China anyway, we’d ended up on a cargo bus of sorts. It was overloaded with large duct-taped plastic bundles and cardboard boxes – the hallmark of the importer/exporter. It left well behind the alleged schedule and the importers/exporters chatted loudly long into the night, and then they snored for the rest of it.

Once across the border, the following day went to waiting in a grim frontier town for the Trans-Mongolian train to arrive. When it pulled in, we boarded in an atmospheric sandstorm.

In incredibly high spirits we went straight to the restaurant carriage for celebratory beers.

Then we made ramen noodles with hot water from the samovar and slept soundly in our bunks for the rest of the sixteen hour journey.

The next morning the train rolled slowly into town. There’s a yurt-city that stretches for a few kilometers on the outskirts of Ulaanbaatar. About three million people live in Mongolia and almost half of them are in UB, as they call the capital on the steppe. The rest of them are scattered around in the Gobi desert, the endless steppe, the taiga.

How to sum up Ulaanbaatar…

We spent the next couple of days looking for a Land Cruiser. UB isn’t an appealing city. Full of karaoke bars and bad food, it’s also got the dubious distinction of being the coldest capital on earth.

We noticed a exorbitant number of warnings about pickpockets, and a corresponding number of second hand phone stores. With ‘Find my iPhone’ turned on, we tracked my stolen phone’s location to a parking lot ringed with dodgy phone shops.

Hiring a car in Mongolia is a fairly casual transaction. We transferred the payment, forked over five hundred USD cash as deposit, and took the keys. When I asked the agent about a contract, she just shrugged. She had a point. We were about to drive this car anywhere we wanted to, on the road or not, and set up camp wherever we felt like it. Why get bogged down in paperwork?

That night we camped in front of a Buddhist monastery in a national park (after managing to drive said Land Cruiser out of Ulaanbaatar). It wasn’t the first monastery we’d camp at, although it was the only one with a sign on the gates to watch out for pickpocketers. We weren’t sure who they meant we should beware of – the monks? Already, there was almost no one else around.

Into the Gobi desert

At over a million square kilometers, the Gobi desert is the largest desert in Asia, and there’s a lot more to it than sand.

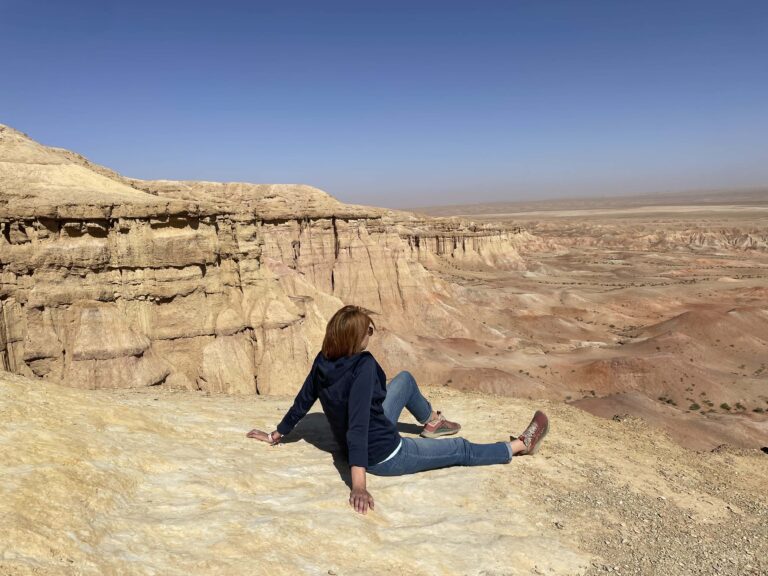

There’s ice: the deep icefield in Yolyn Am canyon doesn’t melt until July, and then it’s back again in early winter. There used to be an ocean. Tsagaan Suvarga, or the White Stupa, was on the ocean floor until the water dried up millions of years ago.

And there were dinosaurs, once. The first discovery of dinosaur eggs was made here.

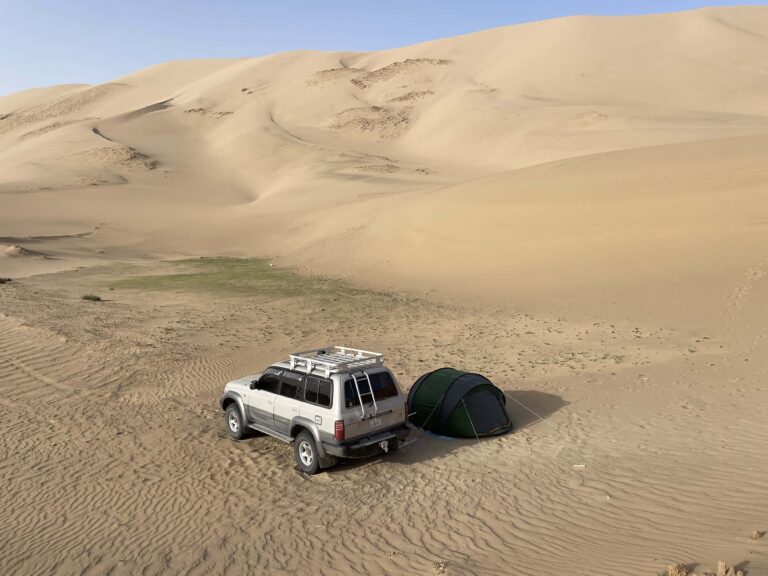

But yes, there’s plenty of sand too. After a day of off-roading on a faint track, we parked the car right in front of Khongoryn Els – the ‘singing sand dunes’. Up to three hundred metres high, the dunes towered over our camp.

The nickname comes from the sound when the wind picks up and the sand scuds along against the dunes’ steep sides. And the wind definitely picked up. Climbing the dunes is a ‘one step forward three steps back’ vertical backslide with a full body exfoliating sandblast.

We hung out in the shade of the Land Cruiser all alone at the foot of the dunes.

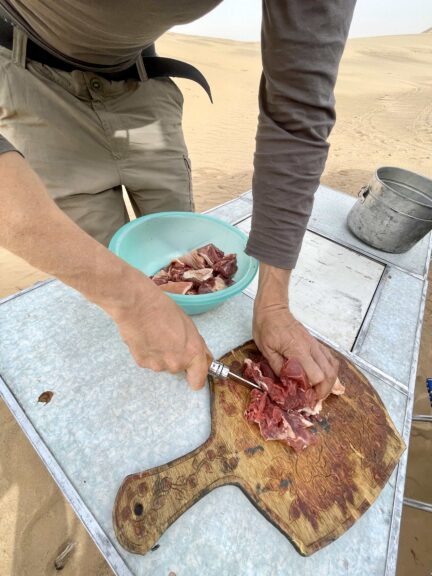

On the second night we cooked up Norwegian farikal from an unidentified piece of lamb. It was ironic. Mongolian food is terrible – there’s a lot of boiled lamb – and here we were boiling up a piece of lamb on our camp stove in our effort to avoid local food at all costs.

Incidentally, the translator app failed us here, too. We’d asked in the shop which part of the sheep it was, but either the girl didn’t know or just wouldn’t say.

The old Mongol capital

Mongolia’s main man Ghenghis Khan united the Mongol tribes in the early 1200s and the resulting empire was actually the biggest in history. It covered up to twenty-two percent of the earth at the time and comprised a quarter of its population, despite Genghis’s army killing millions on the way.

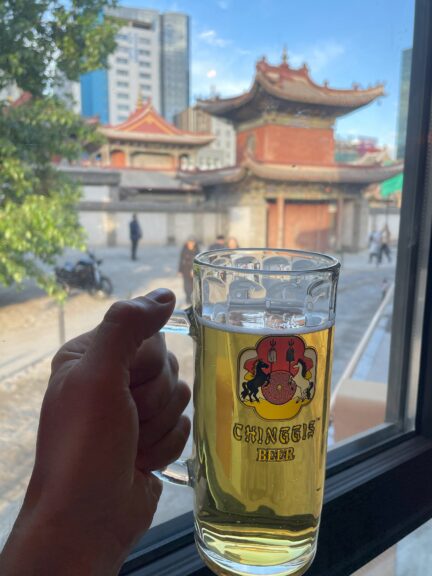

Most Mongolians revere Genghis Khan as the father of their nation and have named everything from an airport to a beer to city landmarks after him.

Today Kharkhorin is just a sleepy little town on the edge of the rolling, stony steppe. For us, it was the only place where we slept in a bed during more than two weeks of camping (as well as the only place we took showers). But in the thirteenth century it was the site of Karakorum, capital of the Mongol Empire under Genghis Khan’s son Ogedei, and no doubt home to hordes of people who didn’t shower much.

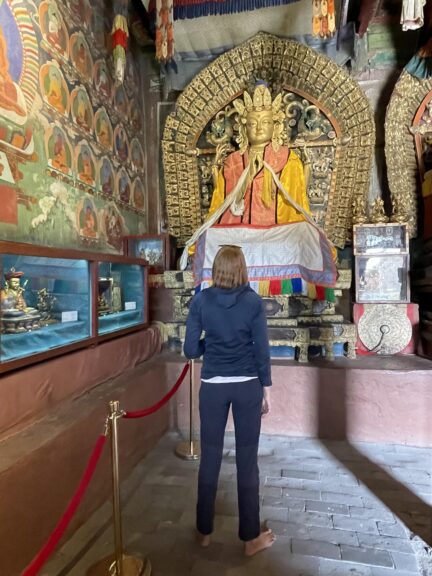

There’s not much left of Karakorum. The Mongol empire collapsed, Buddhism reemerged in the 1500s, and in 1585 Erdene Zuu Monastery was built next to – and pretty much out of – the ancient city’s ruins.

Buddhism flourished, though I’d imagine the same can’t be said of the population, since by the 1920s around thirty percent of Mongolian men were Buddhist monks.

The edge of Siberia

We drove past herds of camels, horses, and yaks – roaming free or corralled by cowboys on motorcycles.

We wild camped anywhere we felt like pitching our tent – next to a volcano, in shady green clearings, on the grass in front of old monasteries in otherwise desolate valleys.

There’s an icy lake on the southern border of Siberia. We camped there too, in doubled-up sleeping bags.

One morning we woke up to a herd of yaks grazing for breakfast nearby our tent:

And speaking of breakfast, we excel at camp-cooking:

Some days we rarely saw another vehicle. When we did manage to come across one, Oyv usually tailgated it relentlessly.

And yes, we inevitably got a flat. We changed the tire but the engine was making an ominous noise. For once we weren’t in the middle of nowhere, but only fifteen kilometers from yet another monastery – with a semi-deserted resort hotel right next door. At the tiny settlement some hotel staff called a mechanic from the next town over. He drove up, shirtless, and grunted something we guessed meant ‘Ok you morons, let’s go’ at us and so we followed him to his workshop.

The translator app came in handy for once, since we successfully used it to drag mostly everyone at the monastery plus the shirtless mechanic and his wife, into our predicament.

Back to civilization

There’s never a bulldozer when you need one…unless someone happens to drop by with one, in the middle of the night.

One night we camped under some trees on a grassy patch faraway from any town. It was a spur-of-the-moment choice. Oyv just turned the wheel and drove straight off the road and about ten kilometers into the hills. Around eleven pm we woke up in the tent to the sound of an engine, and then two voices. They didn’t leave so we unzipped the door and peered out to see a bulldozer loaded on the back of a flatbed truck a few meters away. A very bemused-looking woman peered back in at us.

Oyv: ‘Um…good evening?’

Bemused woman (something in Mongolian along the lines of): ‘Yeah, so you aren’t the ones who asked us to drop off this bulldozer.’

Sar and Oyv: ‘Alright then, goodnight!’

We zippered the door back up and in the morning the people and the bulldozer were gone. Moral of the story: be careful where you decide to pee because even if you think you are alone, you really might not be.

On our last afternoon we drove past a herd of horses, over a little stream, and into some rolling dunes. We set up camp one last time, pitching the tent in the midst of a ring of small sandy hills.

In the morning, we drove the rest of the way back to UB and managed to park the car in the city despite wild traffic. Back to civilization, which in this case meant beds in a guesthouse, hot showers, and Genghis Khan beer.

Read More

For more of our adventures (and misadventures) as we travel from Cameroon to Japan, check out the rest of my stories from the road.

Thinking about taking on this roadtrip yourself? Read this post for our itinerary and lots of practical advice: Self-driving roadtrip in Mongolia: itinerary and planning.

Or if you’re in China and planning to travel to Mongolia by road, have a look at this post: How to cross the border from China to Mongolia.