For us, every Christmas is different. Last year on December 24th we crossed a remote border from Guinea to Sierra Leone on motorbikes, and bought our Christmas dinner while it was still alive. The year before that we were suddenly in Wadi Halfa, a little frontier town in the otherwise empty desert, having just made the trip down from Egypt and into Sudan. The year before that, I had food poisoning in Myanmar, but still managed to muster the strength to go hot-air ballooning – and so on – but those are stories for another day. So we were looking forward to whatever un-traditions we could establish for Christmas 2017 and then totally break with in 2018.

After our visa-run to Ghana we returned to Togo and spent a couple of days chilling out at Lac Togo. We stayed at a hotel which was totally deserted – we were the only guests. It was a nice place and we liked it (although they serve a terrible breakfast, and unfortunately they keep two crocodiles in a cage in the garden), but there just aren’t a lot of travelers in Togo.

So we were really surprised one day when we walked into the garden and saw eight Germans gathered around the crocodile cage with their guide – and two armed guards. We knew the guns weren’t to guard against the docile cadged crocs, so we waited until they’d left the premises and then we asked one of the hotel staff about it (there were a lot of staff there, considering the number of guests). His answer was a bit unnerving: due to the current situation in Togo, with regular anti-government demonstrations plus some ‘problems in the north’ which he did not elaborate on, the government has started assigning armed guards to any organised tour group which does come into the country. As far as we were concerned that was just one more reason not to travel in a tour group.

One day we hired a pirogue – a wooden dugout canoe – to go across the lake to Togoville. The lake is so shallow the boatman doesn’t row the boat; he took us across by a combination of sailing and prodding the pirogue along with a pole like a gondolier in Venice.

Historically speaking Togoville is all about voodoo, but today the focus seems to be more on the big Christian church that dominates the approach from the lakeshore to the village behind it.

We’d arrived in time for market day so we did some shopping.

We decided to move on, so we went to the next border and joined the throngs walking the short distance from Togo into Benin. When we arrived on the other side and held out our passports, the officer smiled and let us take a photo of this sign:

Getting the camera out around a border is heavily frowned upon but we like documenting our crossings whenever we can get away with it.

Continuing our stroll into Benin we walked up the road until we eventually came to what we recognised as the Gare Routiere – the familiar transport hub present in every town, where we knew we’d eventually find a ride to our destination, Grand Popo.

Grand Popo is a sleepy little village on a long beach. We stayed at an auberge set in a colonial-style house, swinging in the hammocks and drinking fresh juice.

We took moto-taxis – or zemi-johns as they are inexplicably known around here – to Lac Aheme. We wanted to do some fishing so we went out on the lake in a leaky wooden pirogue with a local fisherman, Denis.

Denis spoke English pretty well but we still had one or two miscommunications, my favourite being when we pointed to a large group of dressed-up locals on the lakeshore, gathered under a canopy festooned with banners and streamers and flags. It was clearly some kind of celebration and we asked if it was a wedding. Denis looked startled and then concerned and hastily assured us ‘No no! No one has died!’.

And then we travelled on to Ouidah, a small city with an interesting claim to fame: it’s the ‘voodoo capital’ of Benin. When you think of voodoo (if you happen to think of it, that is) you probably think of Haiti; or a little cloth doll with long sharp pins stuck in its back, and a person bearing resemblance to the doll hobbling around somewhere, bent double in agony. But that’s not the real story. Voodoo, which means ‘Hidden’ or ‘Mystery’ originated in Benin, and black magic isn’t a part of it. It’s just another religion, and like other religions it’s also a way of life that permeates culture in art, music and medicine.

During the 17th to 19th centuries European slave traders established trading posts in Ouidah and along the coast of Dahomey, as Benin was then known. Hundreds of thousands of people captured from all over West Africa were shipped as slaves from Ouidah to the Americas. These captives brought their religion with them and over the years it was mingled with some Catholicism. Freed descendants of those slaves eventually brought the new blend back home.

While approximately 25% of Benin’s population is Muslim and another 40% are Christian, most people either practise voodoo or have fused elements of it into their own beliefs. Adherents to the religion consult priests who in turn communicate with the spirits. The priests ask the gods to intervene on behalf of the supplicant – whether it be a wish for prosperity, fertility, good health or good luck. Sometimes they sacrifice chickens or goats, or make an offering of palm wine, and often use herbs and animal bones to make potions and charms. Just like any other religion, it even has its own public holiday: January 10th is Voodoo Day and is celebrated all over the country with singing, dancing, drumming and drinking.

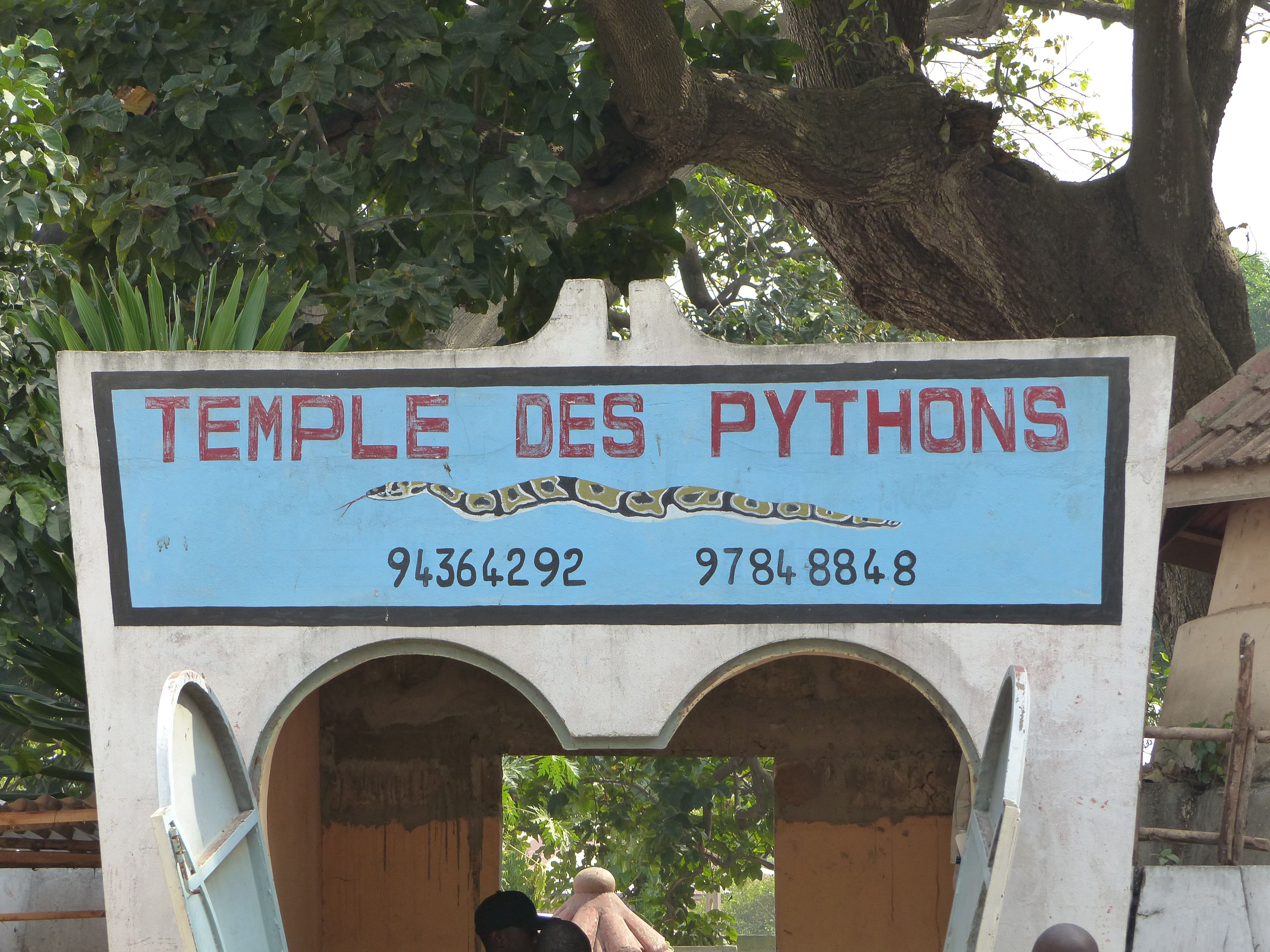

Ouidah means ‘python’ in the local language and so it’s only fitting that the celebrated reptile has its own temple here in town.

Around one hundred and fifty pythons drowse in the temple, sacred to the last one, and the priests let them out once a month to eat. By this I mean that more than one hundred pythons are simply let loose in the city to search out mice or rats, and according to the temple guide they generally slither back again once they’ve eaten their fill. Not all of them come back of their own accord; the reluctant stragglers are gradually rounded up by the citizens of Ouidah and respectfully returned. By our reckoning around seventy pythons were presently unaccounted for and the guide confirmed this when he matter-of-factly mentioned that there were ‘many pythons in the city at the moment’.

Handling the sacred snakes is not a problem and we were let into their enclosure where they lay coiled in heaps in a pit.

On a sidenote, if you look closely at these two snakes below you can see that one has a much larger head than the other. The one with the tiny head is the male.

Out of the snakepit and back into the light of day, we returned to the city streets where a festive party atmosphere was taking over. Crowds gathered as costumed dancers whirled and twirled by, accompanied by frenzied drumming and hornblasting. The dancers were completely covered in what looked like head-to-toe rainbow-colored grass skirts, with carved masks perched on the top.

We had already asked the temple guide about these dancers and their costumes. Newly enhanced religious beliefs weren’t the only traditions freed descendants of Dahomeyan slaves had brought back with them. The costumes and dancing were reminiscent of celebrations on the one day a year that slaves had been allowed off to enjoy themselves, and the masks worn on top were mocking representations of slave traders.

So it was Christmas Eve and we were in Ouidah, voodoo central. The idea of travelling independently in Africa is often loaded with a whole lot of negative connotations. But just as we’ve never been robbed or even encountered anyone who obviously wished us ill, here we were in Ouidah and nobody was sticking pins into dolls that looked suspiciously like us. We sat down at an open air bar and watched life surging in the street around us. After a couple of beers, we returned to our guesthouse. The tropical garden was lit up and decorated for Christmas. The owner poured us glasses of South African wine from his own collection, to go with the lamb we had for dinner and we toasted another unusual Christmas – far away from home but discovering a new place together.

And then there’s New Year’s Eve. But that’s a story for another day.

Read More

Check out the rest of my stories from the road, for more of our adventures (and misadventures) in Benin and Togo.