There’s a tiny Himalayan kingdom tucked away between China and India whose people call it Druk Yul, or Kingdom of the Thunder Dragon. It’s a kingdom where green, stupa-dotted valleys nestle between snow-capped peaks, prayer flags flutter in the wind, and ancient monasteries cling to steep cliff-sides. Surrounded by mountains, it’s like a world of its own. That kingdom is now a constitutional monarchy, and we all know it as Bhutan.

But first, some rhinos

We’d crossed the border from Bangladesh back into India near Kolkata. Not because it fit well with our travel plans, but because it was the only border India would let us cross at all. Ending up at the wrong end of the wrong state, with a deadline fast approaching – the entry date on our short visas for Bhutan – we needed to make a decision. Should we hang out in Kolkata until the last minute, chilling in cafes and eating momos in the street? Or should we head up to Assam, faraway in northeastern India, to check out Kaziranga National Park and its famous one-horned rhinos? We opted for the latter although it was nearly a tie. There was a place near our hotel serving up delicious dosas and we went there every day, both times we were in Kolkata.

We were running out of time, so we booked a flight to Tezpur and hired a driver to take us the rest of the way to Kohora, a village on the edge of the National Park. Then we changed modes of transport again: at Kaziranga the best way to get close to the rhinos is on the back of an elephant.

The next morning we showed up at the park gates. We were on time; a little early, even. Being early, or on time even, is pointless in India. The selfie-obsessed local tourists we were grouped with straggled in eventually. We all clambered onto the backs of some very patient elephants and lumbered off into the park.

Oyv and I have been on one or two wildlife-viewing-type trips before in India, where noisy hordes of tourists instantly drive into hiding whatever remaining animal hasn’t gone extinct yet from sheer frustration. Let’s just say we’d set the bar pretty low, despite going out of our way to fly up here.

But as so often happens, India had a surprise in store for us. The elephant driver sitting in front of me jabbed his heels into our elephant’s leathery neck, just above its shoulders. The elephant stood still and past his softly flapping ears we watched three rhinos graze nonchalantly from our front row (or you could say nosebleed) seats.

One city, two countries

We waited on the side of the road for the bus out of Kohora. It was over an hour late. When it finally arrived, the driver waved enthusiastically out the front window at us. Then he blasted the horn a few times and beckoned us aboard with frantic urgency, as though time was suddenly of the essence.

We spent the night in Guwahati, the closest big city. The next morning we took a train another state over to Alipurdar, debating all the way if we should actually get off in Jalpaiguri. Alipurdar won out and then we found a taxi to take us another hour’s drive to Jaigaon. It’s funny how places we’ve never heard of before – for good reason, there’s nothing to them – turn into vital destinations and we’ll travel for two whole days, obsessing about arrival times and finding rooms, as though these we were places we’d been waiting to visit our entire lives.

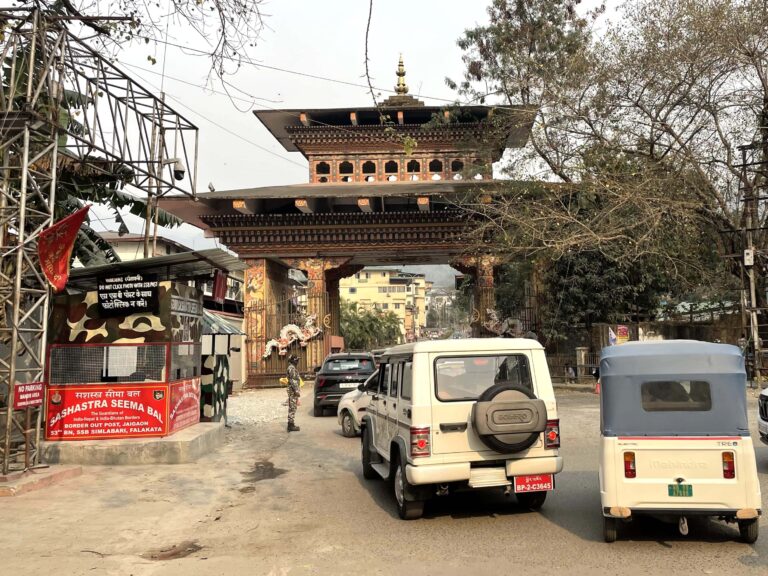

Despite never having heard of it until recently, Jaigaon actually is a place we’ve been waiting to visit for at least the last few years. That’s because Jaigaon is the literal gateway to Bhutan. It’s a city that straddles two countries. The border runs right through the middle of town and there’s a huge, ornate gate where India and Bhutan meet.

We checked into a hotel on a busy, noisy street near the gate. Standing on the hotel balcony in India and sipping lemon sodas that tasted vaguely of hardboiled egg, we looked across the street and into Bhutan.

The rise of the Dragon King

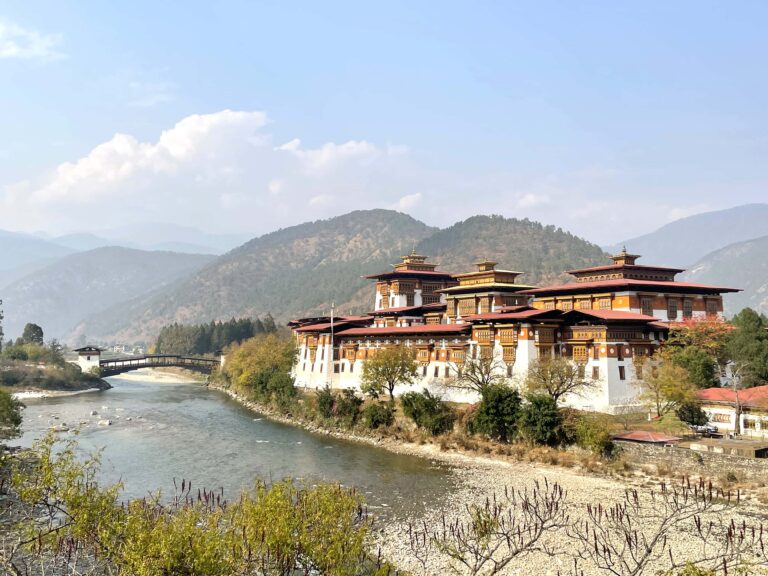

A lot of Bhutan’s early historical records went up in smoke when a fire raged through the old capital, Punakha, in 1827. Steeped in legend, not much is known about the area before the arrival of Tibetan Buddhism around 750 AD.

In the early 1600s a Tibetan Lama called Ngawang Namgyal unified the valleys of today’s Bhutan into a single state, establishing a distinct cultural identity in the process. Also known as the ‘Bearded Lama’, he became a sort of Bhutanese Dalai Lama and is revered to this day. His death in 1651 was kept a secret for fifty-five years, and when the game was finally up, the fledgling state lapsed into conflict.

This fiercely independent nation has never been ruled by an outside power. Bhutan controlled and sometimes fought with nearby Himalayan kingdoms, eventually losing a war with British India in 1865. After signing a treaty to end those hostilities, and the rise of today’s royal house in 1907, the Kingdom of the Thunder Dragon became a British protectorate. Everything changed again in 1947, and Bhutan signed another friendly treaty: this time with the newly independent India. Both countries recognised each other’s sovereignty, and the UN finally recognised Bhutan in 1974.

Bhutan is now on its fifth Dragon King in the Wangchuck family dynasty. King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck ascended to the throne in 2006 when his father abdicated. Before stepping down, the fourth King (who incidentally, had four wives – all of them sisters) basically abolished the monarchy himself. He initiated the first democratic elections and rendered the next King a figurehead with no actual power. Still, the young royal family is wildly popular with the Bhutanese people and the King consistently shows his determination to ensure the country’s successful transformation to democracy.

A different kind of tourism

Indians and Bhutanese can go back and forth through the gate in Jaigaon with only their national ID. In fact, some towns in Bhutan are accessible by road only with a detour through India.

For the rest of us, grabbing a piece of ID and taking a scenic drive won’t cut it. Entry to Bhutan comes with a fee. At the moment, just being in Bhutan costs one hundred USD per person per day, plus the requirement to book a tour and be accompanied by a guide anywhere outside Thimphu and Paro valleys.

All this is the government’s attempt to prevent the outside world from affecting Bhutanese traditions and lifestyle. Maybe they have a point. The population of the entire country is less than 800 000. Television was banned until 1999. Geographically, politically, culturally isolated from the rest of the world for centuries, Bhutan didn’t allow anybody else in until the 1970s. Even now, visitor numbers are very low and Bhutan likes it that way. They call it low-impact high-value tourism.

So we booked a guide and a driver, and paid the fees. Namgay and Nima met us in India and after all the usual border-formalities, we walked through the gate.

As India faded into the distance, even though we could still see it – we didn’t hear it. ‘Honking’s not allowed here’ said Nima, our driver. Free-range cows aren’t allowed either, judging from the remarkably clean streets, and we stopped watching our step constantly.

More Buddhas than people

Thimpu is one of just two capital cities in Asia that doesn’t have a single traffic light. The other one is Pyongyang, North Korea. Rules don’t generally seem to mean as much here as they do in North Korea though. ‘My license expired and I forgot to renew it’ said Nima, as he and Namgay got out of the jeep and exchanged seats for the third time ahead of a police checkpoint on our way to the city.

Thimphu is home to about 100 000 people and they are outnumbered by Buddha statues. The golden Buddha Dordenma stands 169 feet tall, built in 2015 as a 100 million dollar birthday gift for the fourth King. The statue is hollow, and inside it are another 125 000 smaller Buddhas. And counting – for a set donation anyone can add a Buddha to the collection.

Namgay is probably used to guiding tourists who plan their trip months in advance rather than from the back of an elephant. He assumed we’d done our homework. ‘You know Guru Rinpoche’ he said conversationally, as we stood around inside the giant Buddha. We did not. Namgay gestured open palm upwards in the Buddhist fashion, towards a large golden statue of what I’d assumed was just another Buddha who happened to be sporting a skinny black mustache.

In the middle of the eighth century Guru Rinpoche, or Padmasambhava (the ‘Lotus Born’) came from Tibet bringing Buddhism with him. While he was at it he prophesied the future construction of the very statue we all were standing in. Like the Bearded Lama or the ‘Unifier of our Country’ as Namgay persistently called him, Padmasambhava is revered to this day. He’s so venerated in Bhutan that he’s often referred to as the second Buddha and he’s just as important as the first one. Namgay briefly mentioned the Guru’s birthplace in modern day Swat Valley, Pakistan. Swat Valley was once a stronghold of Buddhism, as unlikely as that might seem now.

But all that did sound familiar to us. As we burned our faces off over chilli chicken at dinner that night, we realised that having been to Swat Valley ourselves a few years ago and seen a lot of the Buddhist leavings there, Padmasambhava was one and the same as the famous Guru we’d learned was from the area and therefore we’d been to his birthplace. So in a way we had done our homework after all. We couldn’t wait to impress Namgay with this information first chance we got.

Auspicious numbers, phalluses, and fertility

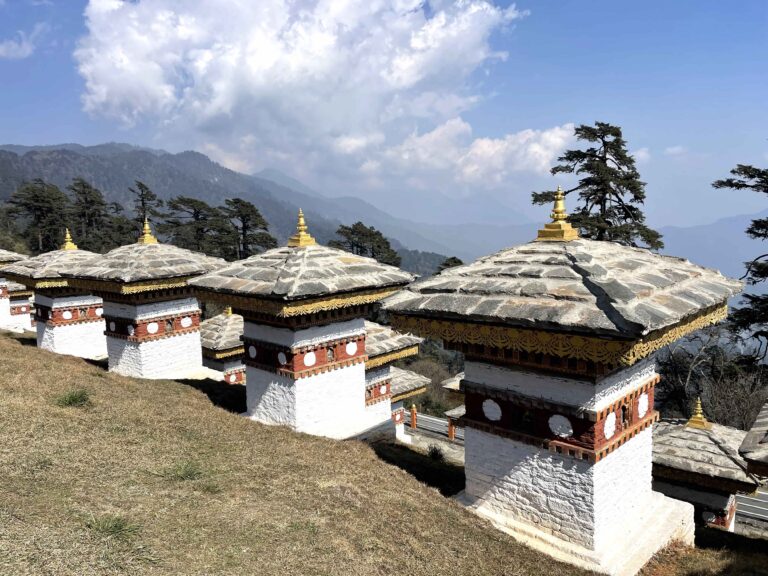

We drove from Thimphu to Punakha through Dochu La, a Himalayan mountain pass. We got out of the jeep to admire the view of the highest peak in Bhutan. Gangkar Puensum is also the highest unclimbed mountain in the world, and it towered over us at 7570 metres. It never will be climbed, either. The government has designated it off-limits, rather than disturb the spirits who live in its distant snowy peaks.

We took a look at the 108 stupas clustered at the top of the pass. They commemorate the Bhutanese soldiers killed in Operation All Clear in 2003, a fight to oust Assamese insurgents who’d established camps inside of Bhutan.

108 is an auspicious number to Buddhists. The path to Nirvana is fraught with earthly temptations – 108 of them to be exact – and so Buddhists have to overcome 108 challenges in life. And I’ll let you guess how many volumes of sacred text it takes to contain the Word of Buddha.

The old royal city of Punakha lies in a fertile valley full of rivers and rice paddies. We made the standard tourist stops. There’s the Punakha Dzong, a fortress/monastery built by the Bearded Lama himself around 1637.

And, one of the country’s longest suspension bridges swaying over the Po Chu river. Visitors are free to stagger across it in the wind.

But that’s not all. Rice paddies aren’t the only testament to fertility in the valley. And dzongs and suspension bridges aren’t the real tourist draw here, either.

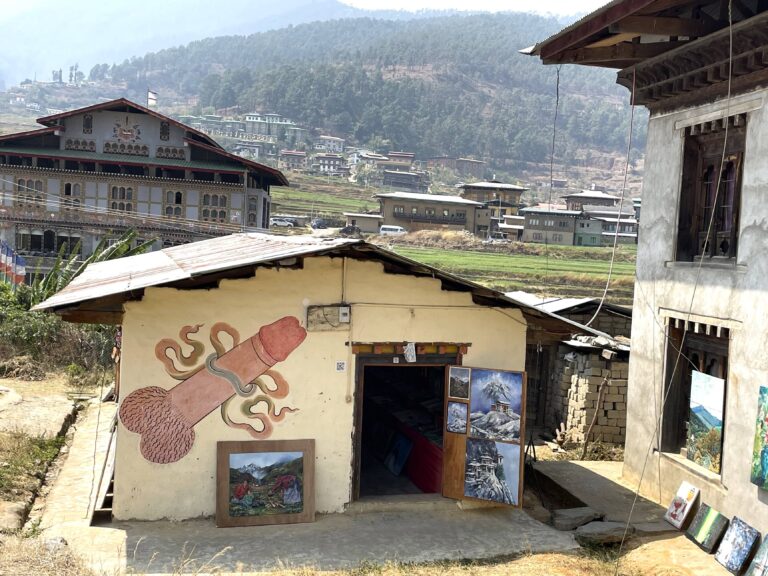

Chimi Lhakhang is a Buddhist temple better known as the Fertility Temple. Drupka Kunley, the erstwhile monk to whom it is dedicated, was born in Tibet in the mid-fifteenth century. It’s not known exactly when he arrived in Bhutan, but he did, bringing a wooden phallus with him. His luggage made his intentions pretty clear. By the age of twenty-five he’d renounced his monastic vows to take a wife, supposedly to show that celibacy isn’t a prerequisite for enlightenment. His unorthodox methods of enlightening others, mainly women, included humourous songs and risque poetry but it was probably the sex part that earned him the title he’s best known by today: ‘The Divine Madman’.

Legend has it that the Divine Madman subdued a demoness with his penis, which had a nickname of its own – the ‘flaming thunderbolt of wisdom’. It’s not clear who came up with that one. The demoness changed herself into a dog but the Divine Madman captured her anyway, exclaiming ‘Chi Mi’ (‘No dog’) as he did so. He built a stupa to mark the spot next to the temple that’s now called Chimi Lhakhang – the ‘No dog’ temple. ‘No dogs to this day!’ said Namgay brightly as we approached the entrance, conveniently overlooking the two or three dogs sleeping outside.

As you might expect of someone whose penis has such an arresting nickname, the Divine Madman is Bhutan’s fertility saint. Women hoping to have a child can visit the temple to receive blessings from the monks. The wooden phallus from Tibet has a handle that makes it perfect for tapping these women on the forehead with. Alternatively, a family-minded woman can carry a large wooden phallus around the temple three times. It has shoulder-straps, and I can only describe it as a penis-backpack. Inside the temple again, she rolls some dice and according to the number – odd numbers are particularly auspicious – the monk announces if the ceremony was successful.

Oyv and I stood in semi-darkness amongst dozens of flickering butter lamps, leafing through a photo album of chubby babies belonging to couples from all over the world who’d visited the fertility temple. I watched as a woman returned from her clockwise trek around the building and a monk helped her wiggle out of the harness and remove the wooden phallus from her back.

Over time, the phallus has become a symbol of not just fertility but also of good fortune. Once you’ve seen it you can’t not notice it: penises painted on walls of homes, carved on the eaves, protruding from door frames.

A huge wooden phallus adorned the dresser in our hotel room. Visiting the temple before check in cleared up a lot of questions in advance.

The omnipresent guru and a hot stone bath

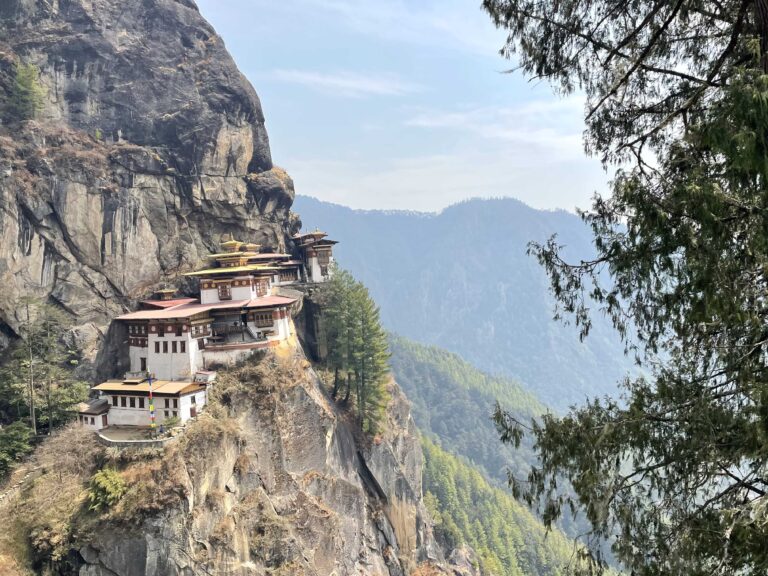

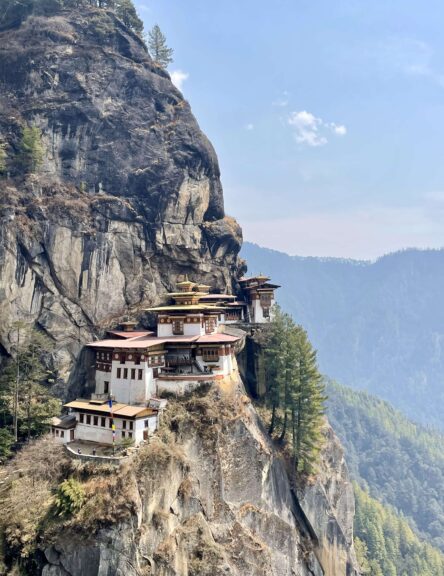

We couldn’t leave Bhutan without crossing paths with Guru Rinpoche again. Paro Taktsang, better known as the ‘Tiger’s Nest’ monastery clings to a nearly vertical cliff nine hundred metres above Paro Valley. It’s believed that Guru Rinpoche flew to this place on the back of a transfigured tigress. He meditated and taught Buddhism in a cave here, and so the monastery was built in 1692.

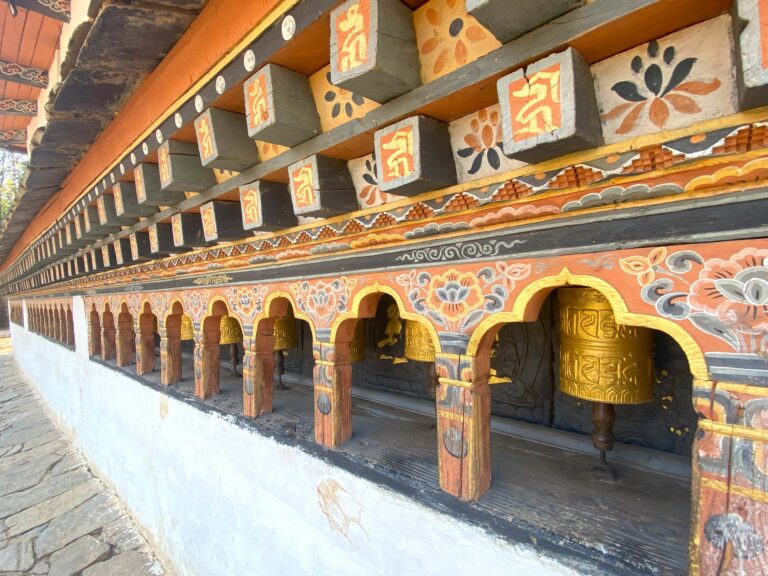

It’s a short walk on a forest path festooned with prayer flags, and then a steep hike up the cliff-side to reach the monastery at 3120 metres.

We explored the cool dark rooms with Namgay, stepping carefully around worshipers prostrating themselves in odd-numbered repetitions. The small spaces were filled with effigies of the mustachioed Guru in his eight manifestations, and we clearly disappointed Namgay with our inability to recognise each one of them.

After a climb like that, why not scald yourself? The Bhutanese use hot stone baths to treat all sorts of ailments. Namgay and Nima dropped us off at a farmhouse in the valley, where the owner was poking at a pile of glowing rocks in a firepit.

He showed us to a room with two wooden tubs filled to the brim with simmering water. At the foot of the tubs was a perforated partition, and on the other side of that – an underwater heap of still-sizzling rocks. We undressed and slipped into the percolating water. ‘If you’re too cold, just shout ‘Another stone!” the owner called through the wall.

Back to India

Early the next morning we piled into the jeep one last time. On the road again, we stopped at another suspension bridge. It’s the oldest one in the country, constructed in 1420. Another one meant for today’s use hangs beside it.

Then we drove for hours through the tiny kingdom in Himalayas, back to the city that has two sides. You can always fly in and out of Bhutan’s single international airport, but we were much happier with walking through the big gate.

Read More

For more of our adventures (and misadventures) as we travel from Cameroon to Japan, check out the rest of my stories from the road.

Or have a look at these stories from our previous visits to India .

This Post Has 3 Comments

Sorry I forgot to comment on the dragons – haven’t heard many sermons-to-date on these mentions. What do you think?

I love reading these stories. Love to you both….xoxo

Thank you so much for sharing. Keep it up and update more information.