Tashkurgan is not a town where there is a lot to do, or where you’d voluntarily plan to spend much time. But it was looking like we might be spending quite a bit of time there, if the length of the queue we’d joined around 7 am for bus tickets to the Pakistan border was any indication. When the office finally opened around 9 the queue suddenly tripled in size – most people were holding space for at least three or four others, and there was total pandemonium.

It was Friday, the busiest day of the week for this border crossing from Xinjiang, a remote autonomous region in western China, into Pakistan’s equally remote and mountainous north. And spaces are limited: for both the border crossing itself, as well as the bus to get there. The border is shut on Saturdays and Sundays, so getting tickets that very day was our only shot or we’d be whiling away a long weekend in Tashkurgan. We’d already spent the previous day travelling from Kashgar on the old silk road, through a gauntlet of checkpoints on a minibus containing a bunch of Pakistani businessmen. They’d joined their colleagues here in this queue, all expats eager to return home for the weekend, and a throng of Pakistani students studying medicine in China. ‘They are licensed killers’ said Sam, one of the businessmen in the queue, when I asked him why they studied in China rather than Pakistan. Apparently it’s a lot easier to get into a Chinese university and graduates can practise medicine freely on their return home, without a qualifying exam.

It wasn’t easy getting to Tashkurgan. It wasn’t easy getting to China for that matter; it wasn’t exactly hard either, but the security, immigration officers, and checkpoints in this region are a marathon test of patience. We’d travelled to Xinjiang from Kyrgyzstan, crossing a border up in the mountains. The Chinese government only reluctantly lets foreigners in there, although they don’t stop us altogether. Even mentioning an intention to visit this part of China on the application will get your visa rejected from the very start, so when we filled out the forms we left out our actual plan to merely nip across Xinjiang and on into Pakistan. Instead we constructed a standard fake itinerary with fake flight reservations to and from Beijing, a few domestic flights, and hotel bookings we cancelled later, for Shanghai and Chengdu (I was really excited about fake-visiting the Giant Panda Center). It was quite a bit of planning for a fictitious trip to a country we didn’t really want to visit in the first place, and definitely the only complete itinerary we’ve ever made in advance.

All this fake stuff is actually normal. Anyone who wants to go to China has to provide the details of their itinerary – any itinerary, that is – whether they plan to follow it or not doesn’t really matter. But the reason for all the secrecy around Xinjiang is something else entirely, and it definitely does matter. Since 2014 China has been systematically rounding up people from a Muslim ethnic group called Uyghurs, and detaining them in ‘re-education camps’. The purpose of the camps is to make the Uyghurs ‘more Chinese’, by forcing them to change their politics and personal identities, and give up their religious beliefs through indoctrination and torture. It’s roughly estimated that 1 to 2 million Uyghurs are now being held in these camps, but China denies their existence and refers to them as ‘vocational education centers’.

So when we left Kyrgyzstan, we went expecting delays. And sure enough it took us about six hours to process a series of formalities, questioning, checkpoints, photographing, fingerprinting, more questions, searches, complications arising from my dual nationalities, and most disturbing – unlocking and handing over our phones for several officers to plug into some sort of device, scan, and scroll through. ‘Where are you from?’ asked every officer Oyv handed his passport to. There don’t seem to be enough Norwegian travellers around for the passport to be easily recognisable and Oyv had to explain his country’s whereabouts every time. Google Translate wasn’t much help:

Immigration Officer (eyeing the passport suspiciously and handing Oyv his phone): ‘Your country name?’

Oyv (speaking slowly to the phone): ‘My country is Norway’

The phone: ‘<Something Chinese>…No Way’.

Immigration Officer: (regards Oyv even more suspiciously, as though he’d forged the passport during the 15 minutes that had passed since the last checkpoint).

Kashgar, our point of arrival in Xinjiang, is a nice place and the old town is pretty. We relaxed in teahouses and ate a lot of good food:

And we looked at a lot of less-good food in the night market too:

But the city bristles with cameras – we counted 43 in a 250 metre stroll. The constant surveillance and facial recognition are part of the Chinese government’s attempts to monitor and control Uyghurs, who are routinely arrested and disappear into camps for nearly any ‘infraction’. Security is a major concern – there are police everywhere, and most shops or businesses have metal detectors, x-rays, and (my favourite) a riot-shield at the ready, apparently for regular civilians to do their part in the event all hell breaks loose in the streets.

For a fake visit, it was an eye-opener. But China wasn’t really on our itinerary, so we went on to Tashkurgan, and joined the queue there for bus tickets to Pakistan.

Clearing Chinese customs we noticed a subtle shift in the atmosphere. We were surrounded by Pakistanis eager to go home. Businessmen and licensed killers alike, everyone wanted to import as many boxes and bundles of Chinese junk as possible, and the strict Chinese order of the day started to give way to a low-key chaos as we all struggled for seats and set off.

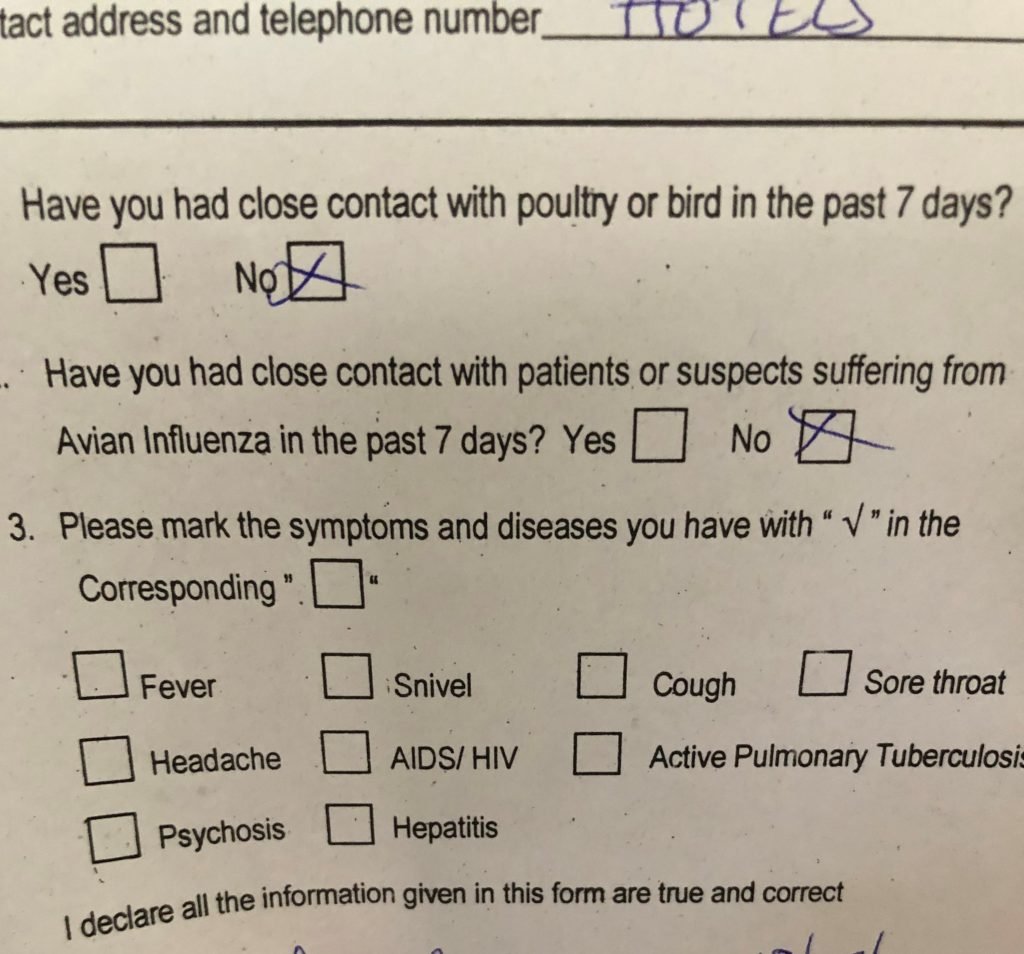

A few final checkpoints later the bus rolled into Pakistan through a massive gate in the mountains, and stopped in a dusty one-street frontier town called Sost. There were none of the Chinese-type formalities here. In fact there were almost no formalities at all: this border crossing appears to run on the honor system. We filled out a healthcheck form where travellers are urged to admit to having any diseases ranging from ‘snivel’ to ‘psychosis’ to ‘HIV/AIDS’.

As the only foreigners we were pulled out of the immigration queue and sent to an office for some casual passport-photocopying, and very unofficial offers to exchange money. An officer stamped Oyv’s visa – he didn’t bother with mine. Reminding us to drop by customs for a bag check he waved us out the door.

But the customs office was shut and locked. Two men stood outside smoking. ‘Your stamp is fine?’ one of the men said to us and we nodded. ‘Your luggages are fine too’ he said, and laughed. ‘Welcome to Pakistan!’ he added, and we stepped out into the street.

Read More

For more of our adventures (and misadventures) in Pakistan, check out the rest of my stories from the road.

And speaking of borders, I’ve written guides with practical info about crossing these two. You can find them here.

This Post Has 4 Comments

Nice to see you on the road again. Did somewhat same trip 11 years ago in opposite directions, after Kashgar east to Golmud,train to Lhasa,bus hitch hike south into Nepal.Rules changed just after this journey. Northern Pakistan beautiful scenery esp in October,.Enjoy.

Thanks:) Interesting…you mean the rules in Pakistan? They’ve just changed again, no more personal armed guards, and loosening up with the NOCs.

Hello sarah, Its really amazing seeing your trip. could you please share the route plan from kyrgyzstan to china kashgar? we are intending for a trip from turkey to pakistan via kyrgyzstan.

Hi, thanks 🙂 Maybe this one would help?

https://whirled-away.com/border-crossing-kyrgyzstan-to-china/