‘Your concern is well-noted’. I read the message in my inbox. Back in those days in Kenya, when I could check my email just like that. Before we went to Eritrea, that is.

We were in Nairobi when we got the bright idea to go to Eritrea. Wannabe visitors to this reclusive hermit nation have two options: apply for the visa at their home Embassy and wait in suspense for at least a month, or wrangle authorization for a ‘visa on arrival’ through a travel agent in Asmara, the capital city.

Thinking we’d need to wait just a few days for the visa authorization, we made our way to Diani Beach on Kenya’s southern coast. It’s not a bad place to be a castaway. In the mornings we went running on the long stretch of white sand.

In the evenings we ate fresh seafood, surrounded by deeply tanned chain-smoking pensioners and elderly sex tourists.

But when we’d waited nearly two weeks we started wondering if we’d ever get into Eritrea. A lot of Eritreans wonder if they’ll ever get out. Over the past decade so many people have fled the country that it’s been called the world’s fastest emptying nation. I emailed the travel agent in Asmara, asking if there had been any progress. He noted my concern and promised our visa authorization was in the works.

From Little Italy to North Korea

Eritrea has changed hands a few times. Italy colonized it from the 1880s until 1941, bringing infrastructure and leaving behind a well-planned capital city. During the second world war the British took over for the next 10 years, while they tried to figure out what to do with it. Then Ethiopia claimed Eritrea as its 14th state, sparking one of the bloodiest wars on the continent. After thirty years of fighting, Eritrea finally achieved independence in 1993. Still, border disputes raged on until about 2018 when both sides signed a peace treaty and declared an end to the violence.

Often referred to as ‘the North Korea of Africa’, ever since independence Eritrea has been a one-party totalitarian regime. Only North Korea itself, and Turkmenistan, have less freedom of the press. Elections have never been held, and the mandatory military service is long and indefinite. Politics are not up for discussion. Locals are wary of saying too much – or anything at all. Anyone and everyone, even the two of us, could be the wrong person to talk to.

In short, Eritrea is closed off and isolated. Getting the visa – did I mention this – is a pain in the butt. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it’s one of the least visited countries in the world.

Languishing at the beach, I checked my email obsessively. And then came the reply from the travel agency. ‘Rest assured, we will send you the visa authorization tomorrow’.

No backpack, big bucks

Since Eritrea’s land borders are shut, flying is the only way in or out. We scrambled around to find half-decent flights leaving Mombasa as soon as possible, and less than 48 hours later we stepped off a plane in Asmara.

Our fellow passengers stormed passport control as one, but we had to hand over our printed authorization and wait some more for this elusive visa. The tiny Immigration office was staffed by ten people sharing three computers. Eventually, the elected English speaker came out and informed us that the system was down. In the meantime, they’d be keeping our passports in a drawer overnight and we should come back to the airport later to try again. Being set loose in the country without a passport, let alone a visa – this surprised me, considering we were in a rigidly controlled police state. I’d more expected to spend the night on the airport floor.

With a last glance at our passports lying on the officer’s desk, we walked into the darkened arrivals hall. At baggage claim it turned out that searching desperately in mountains of bags, boxes, and suitcases is the only way to find your luggage. Eventually we unearthed Oyv’s backpack and discovered that Ethiopian Airlines had left mine in Addis Ababa.

Cabbing into the city, we took stock. We’d arrived! But still no visas and now we were also short two passports. My backpack was living its own life in Ethiopia. I had nothing besides the dress and flip flops I was wearing. Clothes well-suited to a castaway’s life on the steaming Kenyan coast, but wildly unsuitable in hilly, chilly, rainy Eritrea. Major plus: we did have 2000 USD. ATMs and credit cards don’t exist here so you have to bring all the money you’ll need and change it to Nafka as you go. Arriving without cash would actually be a bigger problem than shivering passport-less in the rain wearing a sundress and flip flops.

Side note: we also had toilet paper, which turned out to be a rare commodity.

Don’t worry. We didn’t get arrested for being undocumented aliens, and I didn’t have to freeze for very long. The next day we went back to the airport. It took a few hours and involved a lot of staff, but we got the visas and my backpack. It was easy to find since we actually saw ground crew offloading it when the day’s flight arrived from Addis.

Piccola Roma

With all our possessions collected and stashed at a guesthouse, we were ready to start exploring.

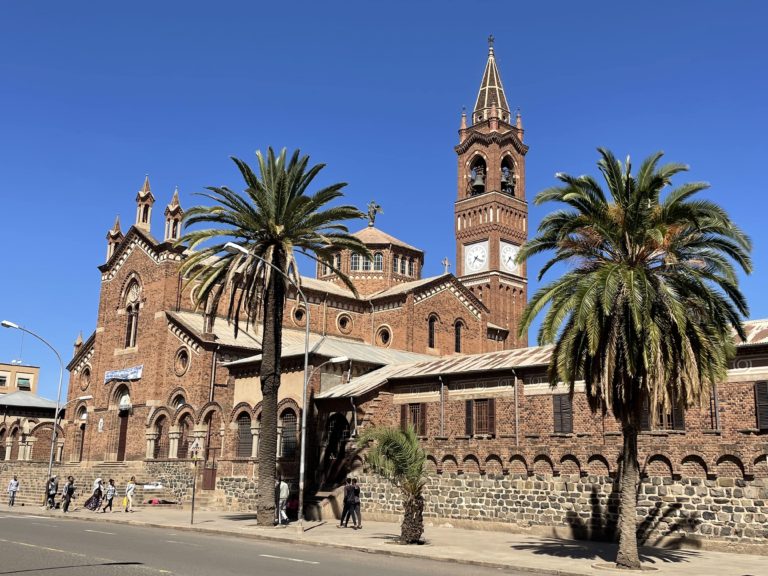

During the second half of the 1930s the Italians went on an architectural frenzy that resulted in a city of avant-garde and Art Deco hotels, cinemas, churches, and cafes. Called ‘Piccola Roma’ in its day, it is still a city unlike any other in Africa. Of course the similarities are there: the power is off all day and running water is sporadic. But it’s safe to walk at night. And cars will stop to let you cross the street, something that hasn’t happened to us in four months.

The best thing to do in Asmara is to take a stroll – a passeggiata, if you like – and admire this little piece of frozen in time Italy.

More indicative of the modern situation are the grandstands facing the street for military parades – the hallmark of many a West or Central African dictatorship we’ve visited lately.

The Italians also left a thriving cafe culture. The city is packed full of cafes and the cafes are packed full of locals sipping macchiatos.

Italian food abounds, but it’s just not as good as the local cuisine. Plus it’s really hard to eat spaghetti carbonara with your hand.

But notwithstanding all the pretty pastel buildings and plates of pasta, Ethiopia was here last. On the edge of the city is a graveyard of rusted tanks and other military vehicles.

Thirty years of warfare leaves a mark, too.

Planning and permits

One day we dropped by the travel agency to thank the agent for arranging the visa authorization. He welcomed us warmly, and over coffee he told us about his efforts to increase tourism to Eritrea. We talked about our plans for the coming days. ‘Let me show you something’ said Tedros, and he booted up his computer. But the power cut instantly, and all the office lights went out. It was noon anyway, so we got in his car and he dropped us off at a local place he recommended for lunch.

We were prepared for this modern-day survivalist challenge to, you know, manage without the internet. Besides completely unreliable electricity, there’s no mobile data in Eritrea. Citizens aren’t allowed to have internet at home or in their offices. Extremely slow Wi-Fi is available only at certain controlled locations – assuming you came prepared, with a VPN, since a lot of sites are blocked. Before leaving Kenya I’d screencapped every useful bit of information I could find.

The government is not content with just tracking internet usage. They want to control where you go in person as well, so we spent most of a day applying for, picking up, and photocopying the permits that would allow us to venture outside of Asmara to the few other places in the country that aren’t off-limits to foreigners.

Keren, the second city

Keren is the cultural heartland of Eritrea and its second largest city. We would have preferred to go by bus but ‘The bus is not allowed. Due to the situation in Sudan’ the girl working at the permit office told us, so we hired a driver to take us there. Efrem had promised to drive us in a 4×4 Toyota Hilux. He’d even shown us a photo of himself standing in front of one. But he turned up – late – in the rattling yellow share-taxi we’d met him in the previous day. I complained pointlessly about the lack of seatbelts, but Efrem just laughed. Seatbelts aren’t required in Eritrea. After all this time we’ve spent in Africa…what else is new.

Eritrea is roughly fifty-fifty Muslims and Christians. Lying in bed in the early morning darkness in Asmara wondering if the water will come on, I heard call to prayer followed in quick succession by ringing church bells. But Keren is mostly Muslim.

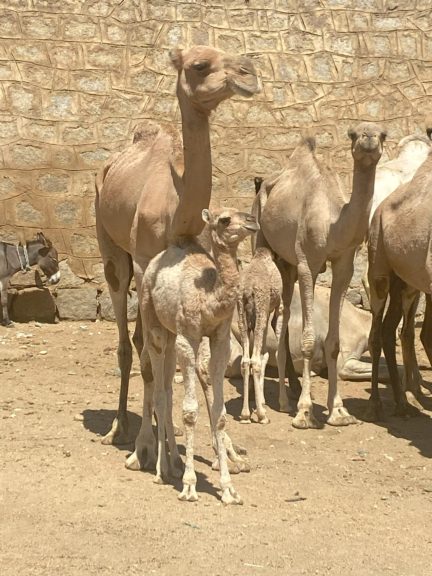

And as Efrem informed us, while Christians don’t buy camels, Muslims do, and that’s why there is a big camel market in Keren every Monday. As the popular saying goes, ‘Looking is free’ so we dropped by.

Efrem played his cards close to his chest. ‘Even she could be an informant’, he said to Oyv, and pointed surreptitiously to a woman selling tea from a thermos outside the market.

Massawa, Pearl of the Red Sea

The permit office gave us a brochure proclaiming Massawa to be the ‘Pearl of the Red Sea’, but that’s not what prompted us to go to this insanely humid coastal town. I was automatically suspicious thanks to a previous visit to Duba in Saudi Arabia, which makes the same claim and is a pretty awful place. But since travel by bus to Massawa is permitted with a permit, we got up early and walked to the station.

Massawa was the Italians’ original colonial capital. While I would not go so far as the brochure, for an extremely depressing ghost town it definitely has a kind of haunting appeal. For starters, the hollow shell of the Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie’s winter palace stands brooding on the harbour’s edge.

Massawa was badly affected by the war with Ethiopia and heavily bombed during a major battle for the port.

People still live in the silent and crumbling ruins of the old town.

From Eritrea with love

We had one last day to spend in Asmara. We bowled a few frames in a vintage bowling alley straight out of the 1950s. A kid manually reset whatever pins we managed to bowl over (I blame the warped wooden floors for my terrible results).

We downed a few more macchiatos and watched Manchester City play Manchester United on the big screen from the upper gallery of the old cinema Roma with a lively crowd of local football fans (another Italian legacy).

Then it was time to go. But not without dropping by Tedros’s office to say goodbye. He didn’t leave it at that though. Having helped us get to Eritrea in the first place, he insisted on giving us a ride to the airport – in the middle of the night – so that we could leave, as he said, ‘from Eritrea with love’.

Read More

For more of our adventures (and misadventures) as we travel from Cameroon to Japan, check out the rest of my stories from the road.

This Post Has 3 Comments

Great post! Well written and interesting, covering a country not well-visited. I was there myself in February, 1994, just shortly after independence. You’ll be surprised and possibly jealous to hear I got my visa in Addis in 2 days and was able to cross overland from Ethiopia (and back) hassle-free. Movement in Eritrea was unrestricted and easy. I was in Asmara for two weeks, a week of it with some UN expats in a cozy house. Went to Keren and Massawa, too. I’d been in Ethiopia at that point for nearly 7 weeks and was thoroughly sick of injera wat so gorged on Italian food, coffee and ice cream in Asmara. Everyone was optimistic and happy, freedom had come at last and aid money was pouring in. It was such a good visit, such a contrast to the way it is now. Ethiopian tourism was in its infancy then (entrance to Lalibela was free and there were no – I mean zero – tourists there at the time. Great post!

Hi, thanks! And yes, I am jealous of just about everything you wrote here:) Not least the part about Lalibela….we were there in 2016 and it was a bit of tourist-mania. At least, it was long enough ago that we were not at all sick of injera this time.

A great overview of your time in Eritrea! Thanks for sharing your interesting experiences and travels!