Note: I originally wrote this post during a trip to India with my sister in 2019. Having been to Varanasi again for the third time in March 2024, something tells me it’s one of those places I’ll just keep on going back to.

Tundla is around an hour’s drive from Agra, so my sister and I left early to give ourselves extra time. The taxi driver talked endlessly into his phone. A transport truck just ahead of us didn’t quite clear the next overpass and with a screetch and a bang, concrete crumbled and rained down on the road. The truck kept going; our driver calmly swerved to one side and resumed his chat despite both of us asking and then ordering him to hang up.

We had a night train to catch. I’ve noticed a lot of people are scared by the very idea of riding a train in India, especially overnight – all sorts of unpleasant stories do abound. Personally I find that speeding down the highway in a taxi with a reckless driver and no seat belts is a lot worse than any train I’ve been on yet.

At Tundla Junction station Goof and I found the right platform and settled down to wait. I bought some chai and sat on the ground drinking it, keeping a close eye on the rat nearby who was watching me just as closely.

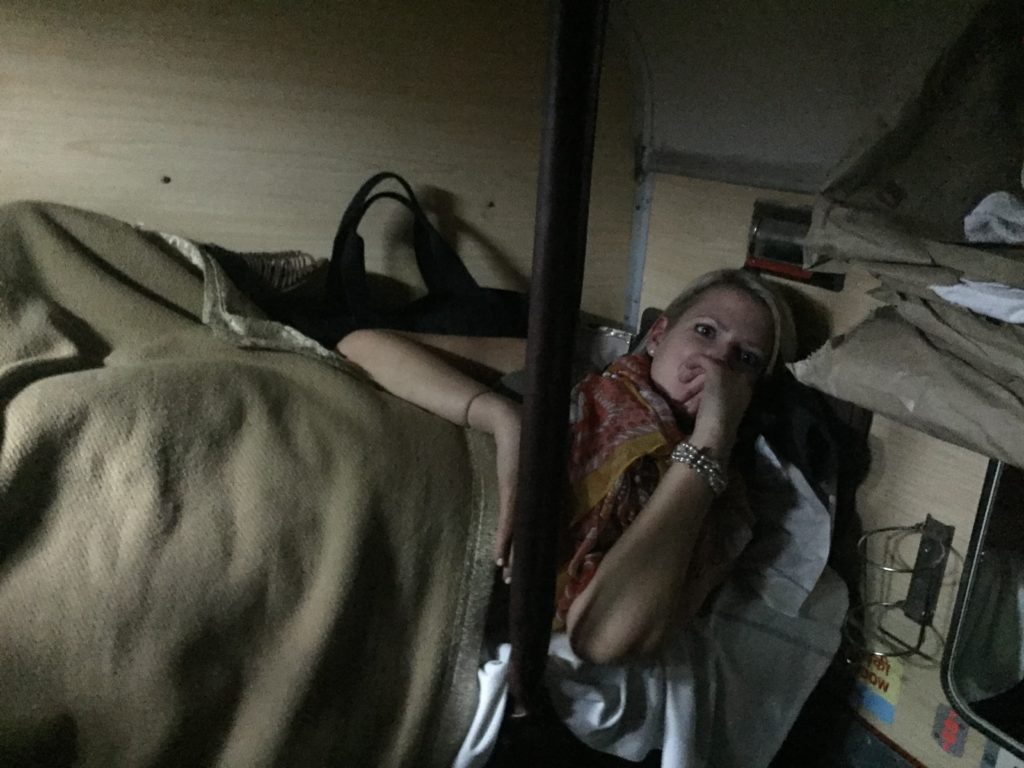

Other than having to kick out another passenger who was already fast asleep in my assigned bed when we boarded in the dark, the train ride was problem-free. My sister and I slept comfortably in our bunks.

There were no thieves, lecherous gropers, food poisoning incidents or any other infamous Indian-train-horrors. I couldn’t persuade Goof to use the toilets under any circumstances though (and it was a 14 hour journey).

We climbed off the train the next morning in Varanasi. Two nearby tributaries flow into the Ganges River: the Varuna, and the Assi. And that’s where the city built in between them gets its name – Varanasi. Standing for centuries on the sacred river’s banks, it’s one of India’s holiest cities. That’s saying a lot in a country that seems obsessed with dedicating all sorts of places and things as holy. Pilgrims come from all over to bathe in the Ganges. And, they come to die in Varanasi. Given the city’s sacred status, what better place on earth is there to leave it all behind?

Goof and I checked into a hotel on Assi ghat. Around eighty ghats, or flights of steps leading from the water’s edge to the city above, line the river’s muddy banks.

My favourite thing to do in Varanasi is walk along the river on the ghats, where life goes on unabated by watchful eyes and passing travelers.

As the day starts, the ghats slowly fill with chai vendors, musicians, hawkers selling flowers and incense, holy men, a lot of animals, and opportunistic touts and beggars.

Any walk along the ghats promises a diverse range of sights, from ritual bathing to washing and drying laundry in the sun:

…and from ganga aarti (river worship) at night time and morning puja (prayers), to cremation of the dead.

At our ghat there’s a pavilion where we watched an old man lead yogic breathing exercises.

Also at our ghat: a Shiva lingam (phallic image of Shiva) that’s a big draw for pilgrims.

We spent a few hours one morning with Mr. Aggrawal, a guide who took us for a walk in the winding alleys that lead up from the ghats, burrowing deeply into the heart of the city.

‘This is a city of Learning and Burning’, said Mr. Aggrawal. As for learning, great scholars have sprung forth from Varanasi: Mr. Aggrawal counted the ways they contributed to culture, religion and education. A centre of Hindu devotion, the city is filled with temples dedicated to Shiva and Vishnu. And, after achieving enlightenment the Buddha gave his first sermon nearby, around 528 BC.

The burning part is more obvious: Goof and I had already been to the cremation ghats and seen the process for ourselves. According to Hindu beliefs, cremating a dead body purifies the soul. In the heat of three or four fires, families stand on the steps with the wrapped bodies of their loved ones and wait their turn. Ashes drift on the smoky air and wood for the pyres is piled high on all sides, strewn with red and gold cloth removed from bodies before burning.

Any walk in the skinny streets behind Manikarnika ghat – the main burning ghat – will involve stepping back and pressing yourself up against a wall to make way for processions of chanting mourners carrying shrouded bodies on bamboo stretchers.

Only male family members participate in a cremation: female relatives aren’t allowed, to prevent too much crying (said Mr. Aggrawal. I’m not sure what the real reason might be). The only women at the burning ghat are those amongst the foreigners watching from a little distance as mourners douse bodies in the Ganges and place them onto funeral pyres. Small but significant last moments play out in public view: we saw one man (probably the oldest son) unwrap a dead man’s face and put his glasses on him.

Members of the lowest caste manage the funeral pyres. They stoke the embers violently, churning up bones and body parts with the glowing sparks. It all happens fast: a body is usually cremated within twenty-four hours of death, and takes around three to four hours to burn. Hip bones and sternums don’t burn that well, Mr. Aggrawal pointed out. Ashes and heavy chunks of bone: it’s all thrown into the holy Ganges after.

Up to eighty bodies a day are cremated on the ghats, but not everyone is a candidate for burning. Those whose spirits are already pure, such as babies and pregnant women, go into the river whole.

By dying in Varanasi a Hindu achieves ‘moksha’. That is, their soul is released from reincarnation, the endless cycle of birth, death and rebirth. Sick and elderly pilgrims travel to Varanasi and stay in hospices for the dying next to the burning ghats, waiting their turn for salvation.

As Mr. Aggrawal said, ‘People are dying to die in Varanasi’.

In between sunrise and sunset wanders on the ghats, Goof and I spent time every day exploring the city’s twisting and turning bazaars, crossing busy streets at a run. Traffic is terrible – other people might be dying to die in Varanasi, the two of us, not so much.

But life goes on like normal here, too.

Varanasi has plenty of cool cafes to chill at.

There’s always chai.

Not to mention animals wearing clothes, snuffling in the warm ash on the burning ghats (ok…maybe that’s not ‘normal’).

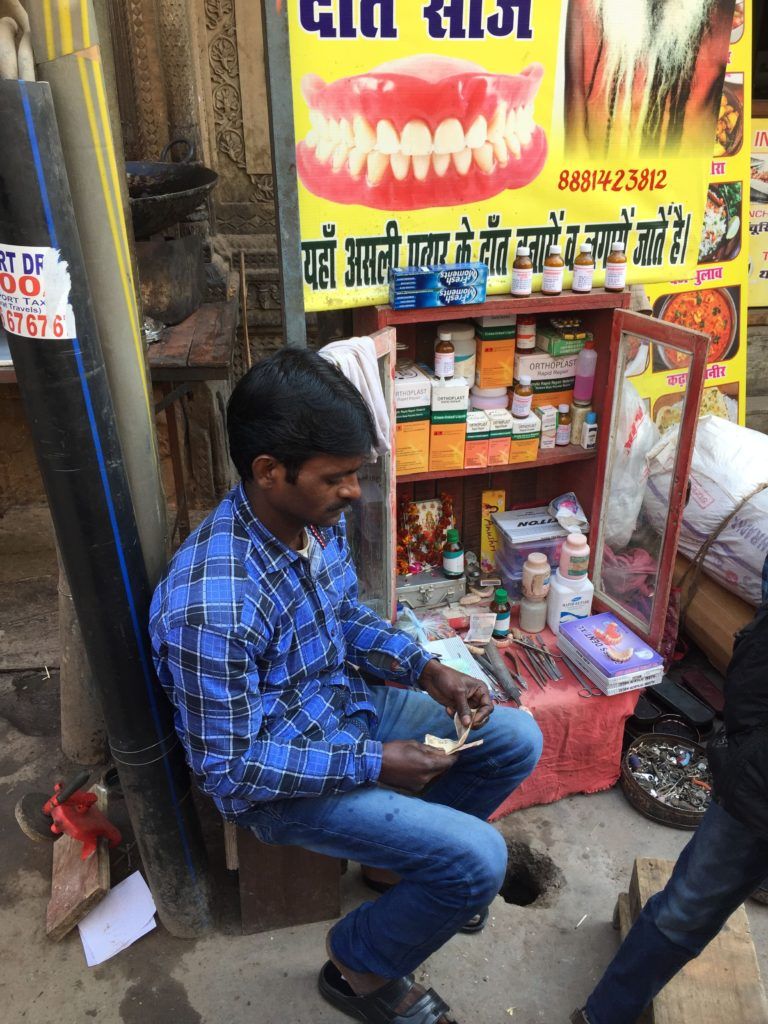

How about some streetside dentistry then? Apparently this man has no degree or qualifications whatsoever, but years of hands-on experience.

I ate delicious streetfood for two (Goof is more skeptical when it comes to food).

And we got some beautiful henna.

Varanasi’s also called Kashi, or ‘City of Light’. The name refers to its historical significance as a centre of culture and spirituality, but also….there’s a beautiful sense of stillness in the early morning, as the sun rises over the river and the crumbling buildings teetering on the ghats take on a honey coloured glow.

Something not to miss in Varanasi is rowing on the Ganges at sunrise (Goof and I managed to miss this). But we did the next best thing, which is rowing on the Ganges at sunset, admiring the City of Light reflecting on the peaceful water.

And Goof actually did some of the rowing herself, too.

Mark Twain wrote that Varanasi, “…is older than history, older than tradition, older even than legend, and looks twice as old as all of them put together.” It only takes stepping off the train to see what he meant. Although most of the buildings standing today are just a few hundred years old, there’s been a civilisation here weathering time – learning and burning – for around three thousand years. Life and death steeped in ancient ritual on the banks of a holy river, it’s India in all of its startling glory.

Read More

For more of my adventures (and misadventures) in India, check out the rest of my stories from the road.