Getting out of China was a relief. It’s not like they tried to prevent us leaving. But we spent so much time at checkpoints manned by unfriendly officers, who scrolled through our phones and searched our bags and asked the same questions again and again, that it started to feel like we’d done something wrong and they were trying to catch us in a lie. Overall, we were happy to go. Across the border and at the top of the Karakoram Highway in Pakistan, we revelled in the freedom to do what we wanted without the police breathing down our necks (as far as we knew, anyway. Apparently they do like to keep an eye on foreigners).

There are various ways to get down the Karakoram Highway. You can travel by death-defying buses and shared jeeps, for example. But any trip on this highway – the highest paved international road in the world – will involve at least a little bit of hiking. That is, traditional hiking on foot, and hitchhiking. As it turns out it also tends to involve transacting a lot of casual business with strangers and at least one of their cousins.

Hitching a ride is easy. We never had to wait on the side of the road more than a few minutes before somebody picked us up and drove us to the next town, asking for nothing more than our opinion on Pakistan. Regular hiking often proved a lot more difficult, thanks mostly to the scorching sun.

After crossing the border we went straight to Passu, the next village. Our guesthouse was right across the road from a string of needle-like spiky mountains called the Cathedral Peaks.

Nothing happens in Passu and it is one of the most relaxing places on earth. But watching the Cathedral Peaks turn pink and gold at sunset is not the only thing to do around here: there is also the ‘World’s Scariest Bridge’ (in fact there are two bridges competing for this title). So we spent our first full day in Pakistan wandering around in the hills high above Passu, often lost, or caught in thorn bushes, occasionally stumbling into little pockets of village life, and climbing down the steep side of a ravine to cross not one but two bridges made of splintered wooden planks strung on rusting steel cables nearly a metre apart in places.

One morning after breakfast we hitched a ride out of Passu to Karimabad. The ‘tourist town’ of the area, Karimabad is a nice little place with some restaurants and two old fortresses, very few tourists, no ATM and just one moneychanger. I mention this specifically because we were running short on rupees. Asking around we learned that the only place to change money was at the hotel down the road, so we went over there and asked the receptionist at the front desk for the rate. He called his cousin and after some discussion the cousin agreed to come over and change our USD. The rate was bad but we didn’t have much choice – the receptionist’s cousin apparently has the final word on moneychanging in Karimabad.

A major attraction in the area is Lake Attabad, also known as the ‘World’s Bluest Lake’. The blue comes from glacial silt but this beautiful lake shouldn’t be here at all, and it wasn’t, until a disastrous landslide in 2010 killed twenty people and blocked the river. The resulting flood created the lake, wiping out villages in the process, displacing thousands of people, and submerging twenty-four kilometers of the highway. We learned all this from our latest host-on-wheels, as we rode from Karimabad through seven kilometers of tunnels newly built in 2015 to re-establish road access to the region. Hitchhiking is a great way to get an unofficial tour on the way to your destination, too.

Now, the lake is a big draw for local tourists. You can jetski here, or sit on the shore eating fastfood at a series of hideous shacks. Or, you can hire a brightly painted boat and just drift out onto the water between the towering rock walls, far away from the crowds.

A little more hitching and one of the death-defying minibuses brought us further along the Karakoram Highway to Gilgit, from where we planned to go to Astore Valley. We knew almost nothing about this valley, other than that transportation is limited and relying on hitchhiking could be, well, unreliable.

When we mentioned this problem to the owner of our hotel in Gilgit, he immediately suggested he’d call his cousin. Enter Abdul, a local travel agent who we recognised because we happened to have a scanned photo of his ID. Abdul recognised us too, from the copies of our passports in his possession. You are probably wondering why we had exchanged copies of our legal ID with a total stranger in Pakistan. Our visa applications had nearly been rejected in a series of random hang-ups with the new e-visa system: at the very last minute the Embassy demanded a letter of invitation after orginally saying it wasn’t required. We’d found Abdul’s agency online and he turned a letter around in half a day, the contents of which informed any interested parties that he’d planned a two week tour for us. He’d done no such thing, but without the letter we’d not have gotten the visas, and that’s why we all had each other’s ID.

Since we liked Abdul, and that’s the way things go here, we decided we’d hire a jeep from him to get to Astore.

At first we thought we’d self-drive. Abdul was fine with this plan. In fact, he was fine with pretty much any plan Oyv or I suggested. He agreed that self-driving was best for us; then when we wondered about taking a driver, he suddenly felt that might be the best solution. Abdul was not a lot of help, actually. Other than with inviting people to Pakistan – according to Abdul himself, he invites around 80% of the foreigners who end up here.

I asked about insurance for the car, already knowing the answer: there isn’t any. Oyv threw the idea of a contract out there. ‘There’s no contract; you just take the car and go’, said Abdul. We thought about this, and decided we’d take the car and go – with a driver, who we could dump legal responsibility for the car on. The driver turned out to be one of Abdul’s five brothers, also named Abdul. It’s a family middle name and all the brothers share it with different first names. It quickly became apparent that we were basically hiring Abdul’s brother to drive us in Abdul’s own car, out to Astore Valley – where we also ended up staying at the Abdul brothers’ family home.

The road to the valley snaked in hairpin turns up and along the side of the mountain, narrow, crumbling, and clogged with drivers who clearly didn’t care at all about things like insurance, or returning from their trip alive.

Abdul shrugged when I mentioned that riding on the roof of an overloaded minibus at high speed in the mountains could be lethal. He didn’t see a big problem with it – he knew ‘only two people’ (one of them his own uncle) who had died riding in this fashion.

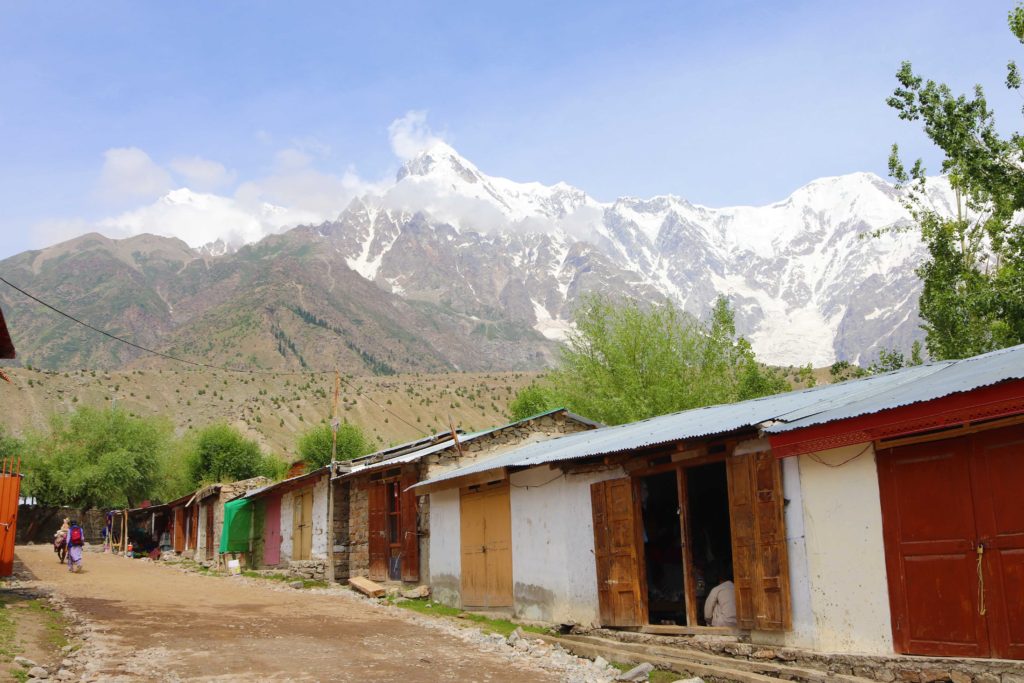

And so we wandered from one valley village to the next, among some of the world’s highest peaks, surrounded by alpine lakes and glaciers, stopping for chai in people’s homes and eating channa and parathas at every meal.

We slept on the floor at Abdul’s house one night; the next night we camped, at around 4000 metres.

Abdul slept in the jeep, with his cousin who had inexplicably joined us on the second day, riding shotgun and playing mournful religious music on his phone. Sometimes the cousin took selfies with me in the background when he thought I wasn’t looking. Waking up in the cold morning we saw that Abdul had mysteriously moved the jeep in the night so that it was parked between the trail and our tent. ‘There are snow leopards here’ he said matter-of-factly as we stood around drinking chai.

Back in Gilgit on our own we ate in a street stall and talked about our next move. We’d leave the peace and quiet and cool air of the mountains behind. No more hiking of any kind, for the moment – just fifteen hours on a bus down from the mountains, to Islamabad.

Read More

For more of our adventures (and misadventures) in Pakistan, check out the rest of my stories from the road.

This Post Has 3 Comments

I found your article very informative. Do keep posting such articles! Thank You.

Great article! I’m travelling the KKH in a couple of weeks and can’t wait to live the famous Pakistani hospitality along with the most beautiful crunchy mountains and cones of the world.

Anyway, thanks!

Thank you:) Have an amazing time!