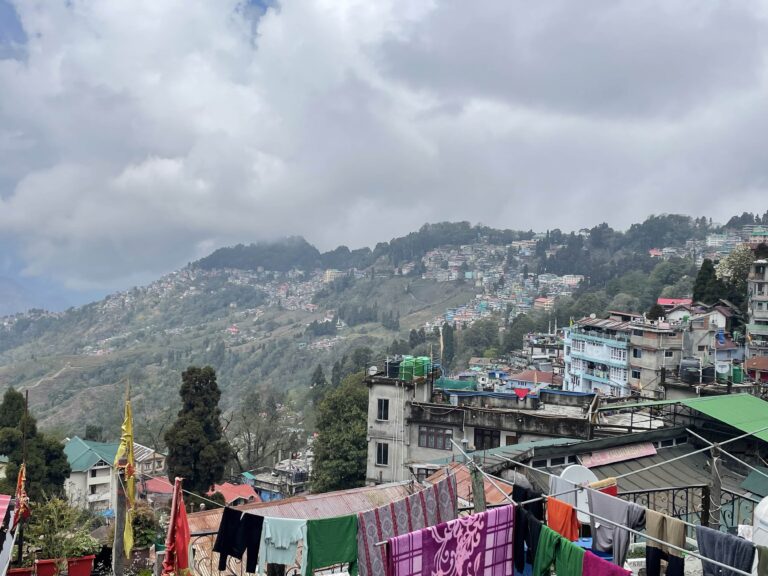

Early one morning in Jaigaon we piled into a shared jeep to Darjeeling. It should have left around seven am but none of the other passengers turned up. It was cold and apparently they didn’t feel like walking to the jeep stand. The driver seemed to know each passenger’s whereabouts so we drove slowly around town, collecting them one by one. When the jeep was finally packed full, we set off on an increasingly steep road overhung with darkly ominous clouds.

The driver was in high spirits: he sang loudly for a long time, and then announced ‘breakfast time!’ and pulled over at a little brick cafe clinging to the side of the hill. We went in and ate some daal and roti. Returning from the wretched toilets behind the cafe, I passed a wet dog lying mournfully in the mud and said hello to him. A man standing nearby remarked helpfully ‘That’s a dog, madam’.

As we reached the old British hill station the skies opened and the rain poured down in sheets. After two days it showed no signs of stopping. We’d planned to spend some time in Darjeeling, riding the toy train and sipping afternoon tea in colonial hotels, but we’d got soaked through on arrival and were now constantly damp.

So we took another jeep back down the hill to Siliguri, and caught a night bus to Patna. That broke down early in the morning and left us standing on the side of the road. When another bus trundled by, we staggered aboard half asleep and slumped in the aisle the rest of the way into the city.

The sun came out in Patna but we didn’t. Before breaking down, the night bus had stopped in a hectic rest station with dubious hygiene. I’d eaten some daal tadka anyway and paid for that mistake with a day spent in bed in a dingy guesthouse.

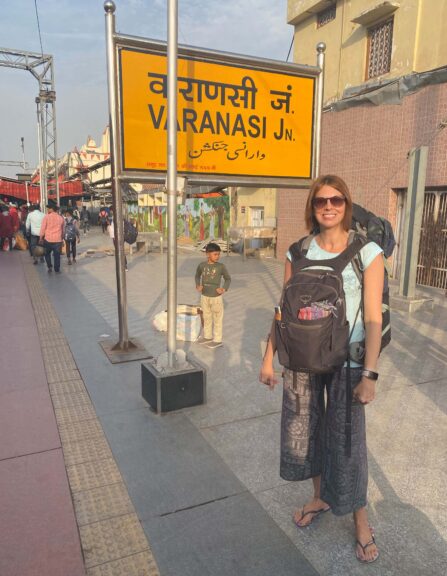

The next morning we took a train to Varanasi. We checked into a rambling old family-run hotel looking out over the Ganges and stayed for five days, soaking up the sun and taking early morning strolls on the ghats.

That’s all, folks

And then Holi rolled around: the famous celebration of colour, love, and spring.

But unfortunately surrounding this festival the subject of where, when, and even if it’s safe for women to participate is a real topic because in India an event like Holi often means huge groups of extremely drunk men.

We ventured out into the crowded streets and were soon doused in colour. The atmosphere deteriorated quickly though, and we had to retreat inside. But not before Oyv revealed a side of himself I’ve never seen. A man grabbed my crotch; Oyv chased him down the street and put him in a chokehold. Shortly after that, another man shoved his arm down the front of my shirt, got his hand into my bra, and wouldn’t let go. Stunned, I tried to pull his arm out but Oyv was faster. He hauled the groper off of me, and as I pulled myself together I looked over to see Oyv screaming in his face and throttling him against a wall.

It was kind of an inauspicious end to our time in India. Our visas were on the brink of expiration and we needed to get going, or risk adding an overstayed-visa-debacle to the list of crappy things that had happened recently.

And so with only a day left on our visas, we traveled to the closest India-Nepal border crossing. At passport control the officer decisively slammed the exit stamp down on our visas and we were finished – for the moment – with India.

Buddha has a hometown too

Across the border, we stopped for the night in a little town called Lumbini. We were tired and hungry, but there’s more to Lumbini than just a comfortable bed for travelers leaving India in haste but still wanting to eat at an Indian dhaba.

According to Buddhist tradition a prince named Siddhartha Gautama was born here in the 6th or 5th century BC. When the prince saw the extent of human suffering just outside the palace gates, he renounced his privileged lifestyle and set off to seek enlightenment. Adopting the life of a spiritual ascetic, he meditated and preached his way to nirvana, eventually becoming known as the Buddha – the ‘awakened’ or ‘enlightened’ one.

While he was at it, the Buddha designated his hometown as one of the four most sacred sites for his followers. Pilgrims flock to Lumbini today to visit the site of his birth and modern temples built by Buddhist associations the world over.

This also explained the number of meditation centres we’d noticed on the bus trip in.

Deja vu in Kathmandu

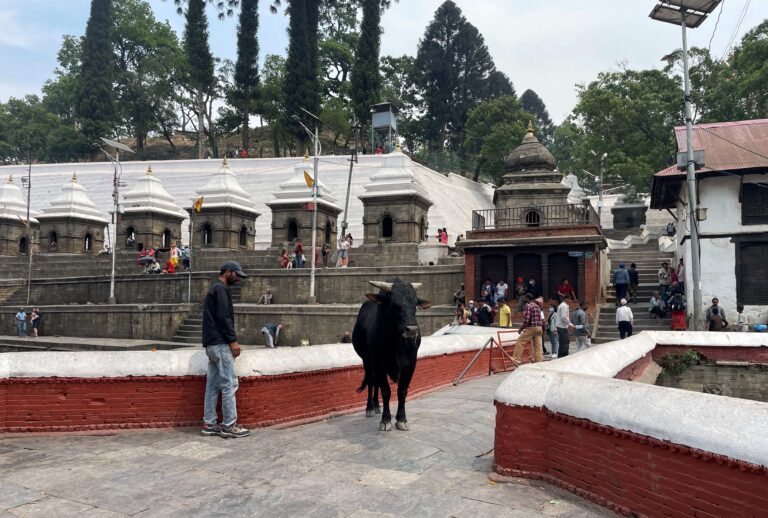

Despite such an auspicious link to Buddhism, the major religion in Nepal is Hinduism. Kathmandu, the capital city, bursts with Buddhist and Hindu shrines alike.

Anyone feeling even a tiny bit nostalgic for India can head on over to Pashupatinath for example – the oldest Hindu temple in Kathmandu. A huge complex devoted to Shiva, it’s been here on the banks of the Bagmati river in one form or another for more than a millennium, although what stands today was built in the 1600s. There’s a Shiva linga in the main temple and as non-Hindus, we couldn’t go inside to look.

But anyone can watch another sacred rite here: public cremation on the river ghats. If you’re coming from Varanasi, this is a familiar sight. Cremation generally takes place the day after death, and the final preparations are carried out here by the deceased person’s family.

We sat on the steps of a smaller shrine opposite, and watched some people shift a body from a stretcher onto a slab that slanted downwards to the water. Some of them gently uncovered the dead woman and washed her feet and hands in the river water. Other relatives hovered anxiously on the periphery, occasionally stepping forward to give a direction or move a limb. Then they wrapped the body back up in shiny orange cloth, and draped the shroud with garlands of marigolds.

The mourners lifted the body together back onto a wooden pallet and carried it to a pyre. Burning takes around four hours. Families sit and watch as the black ashes are swept into the river and drift away. It’s the most auspicious ending a Nepalese Hindu can hope for.

Once upon a time in a Himalayan kingdom

Nepal was a kingdom, once upon a time. But revolution led to democracy in 2006, and the monarchy was abolished two years after that.

I’d never heard of the Nepalese royal family before. They were so obscure to me that the story of their demise didn’t even ring a bell. In a fate on par with that of the last Russian Tsar, nine members of the family including the King and Queen were massacred at a royal residence in June 2001. The subsequent investigation found that Crown Prince Dipendra opened fire on his family during dinner, and then shot himself in the head. Despite all that, and the fact that he was in a coma, Dipendra succeeded his father as king, but died in hospital three days later. His father’s brother Gyanendra was declared king after that – the last one as it turned out, to be deposed seven years later.

Potential motives abound including resentment over a thwarted marriage to an Indian heiress, but many suspect the Crown Prince wasn’t the shooter at all, and that it was a palace coup staged by Uncle Gyanendra. We’ll never know: the spirit of the dead king was exiled from Nepal in a Hindu ceremony and eventually the entire royal family was relegated to history. The ex-king is just another commoner and his palaces are now public museums.

A day in Thamel and you’re ready for anything

The capital was turning out to be a pretty interesting place. And of most interest to us (aside from all the breakfast cafes and streetfood): at a height of 1400 metres itself, Kathmandu is the gateway to the Himalayas. We’d already planned to do a bit of hiking, of course. Nepal is nothing if not mountainous – eight of the world’s highest peaks are found within its borders.

Let me interject: we’re traveling for a year. We’re carrying two huge backpacks with all sorts of stuff in them – an aeropress coffee maker for example, and at least 500 grams of coffee at any given time. What I have got: a hair straightener. What I haven’t got: anything suitable for high-altitude hiking, other than a wool long underwear suit.

Neither of us was enamoured with the idea of hiking for days with a guide and yet we didn’t relish the prospect of getting lost in the mountains with a hair straightener and an aeropress, either. We asked the owner of our guesthouse in Kathmandu if he, as a former guide himself, thought we should hire one. Our host seemed unconcerned. He tried on one of my shoes and scraped it over the pavement like a restless horse pawing the ground. Satisfied with the treads, he reckoned we’d be just fine. Pushing aside the thought of waiting on a peak for a helicopter rescue (albeit with straight hair and freshly brewed coffee) we decided we’d trek Langtang Valley on our own.

Ill-equipped for high-altitude trekking on a whim? No problem. Thamel has you covered. Kathmandu’s most famous backpacker neighborhood is a messy bazaar stocked with endless souvenirs from ropes of glossy prayer beads to soft cashmere ponchos (not to mention constant offers of hashish). Outdoor equipment stores sell real brands and fake copies of everything you’d ever need for activities ranging from an afternoon stroll to summitting Everest. I bought a maybe-Maamut coat, and a not-so-much North Face muffler, and so on. We aggressively bargained for rental sleeping bags and hiking poles, and a mid-sized backpack to carry it all in, and off we went.

Himalayan hiking

We got a taste of the mountains ahead on the bus ride to Syrabru Besi, the little village on the edge of Langtang National Park. I was sure the road was worse than the trek itself could possibly be. It involved teetering on hairpin bends of the sort that made me close my eyes, although I noticed that other passengers seemed to relish the views of certain death, should anything go wrong.

After a night in a somewhat dirty guesthouse, we were rested and ready. Early the next morning we set off for the trailhead and spent seven days hiking Langtang valley, stopping each afternoon for food and a bed in the teahouses strung out along the route.

On day two we reached Langtang village. It lies above 3000m, the height where altitude sickness can set in. That night our teahouse was abuzz with discussion of symptoms. A trekker from New Zealand worried about the intensity of her headache. A group of Germans sitting around the wood stove complained they felt short of breath and wondered how fast was too fast, as far as racing hearts go. I suddenly wondered if my chest was actually constricted, or if I just imagined it. An Israeli doctor (or rather just a hiker who seemed to know a lot and had a medical device with him) went around and checked everyone’s heart rate and blood oxygen levels. But all that’s nothing, really.

On April 25 2015 Nepal was struck by a devastating earthquake that flattened entire towns, destroyed history, and killed 9000 people. In Langtang valley it triggered a landslide and a glacier came crashing down, bringing tons of stone and earth with it. Langtang village and its inhabitants were wiped out in a matter of minutes. Only one building was left standing. An estimated 310 people lost their lives, mostly Langtang residents and around eighty foreign trekkers.

The survivors were evacuated, but they returned eventually and built a new village just above the ruins of the first one. They restored the teahouses and trails and brought life back to the valley. But they didn’t forget. There’s a memorial nearby, strung with prayer flags that flutter over plaques listing the names of the dead, and photographs occasionally placed by families along the route where bodies were recovered.

Namaste, Nepal!

We hiked on in bright sun and sharp wind. The trail got steadily steeper and the air got noticeably thinner. We passed shaggy yaks grazing next to the trail, herded and hounded by big loping dogs.

Green forest paths and rushing streams gave way to scrabbling over barren scree and piles of boulders. We said hello to porters and dodged donkey pack-trains, peeked into shrines, and gave prayer wheels a turn.

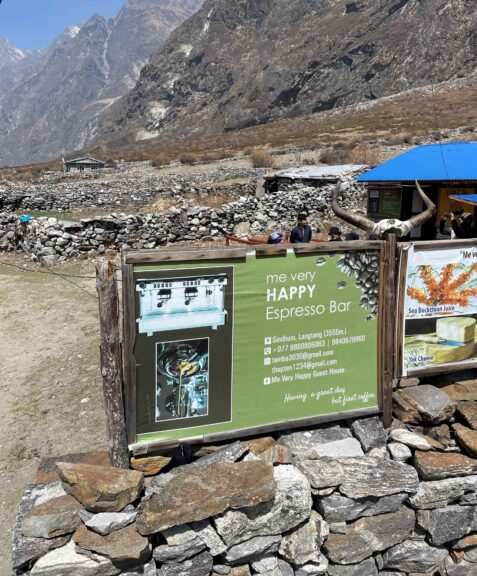

On the third day we reached Kyanjin Gompa. At 3800m the village sits at the uppermost end of the trail and trekkers use it as a base for climbs to surrounding peaks that towered over us on all sides.

There’s a cafe there serving pineapple upside-down cake among other retro favorites, and good coffee which was convenient since after all, we’d left our aeropress way back down in Kathmandu.

The cafe was packed with hikers and we listened in on conversations about Everest, glaciers, blood oxygen levels, and helicopters. It was a lot colder now too, and I started wearing my wool long underwear suit around the clock.

![]()

Starting from Gompa, we climbed high enough that sometimes we trudged through mud, or snow and ice. Sometimes heavy mist rolled in and we couldn’t see the bottom of the valley. From the safety of the foothills we watched snow thundering in minor avalanches down distant mountainsides.![]()

And then we had our best day in Nepal. From Kyanjin Ri, at 4700m, we looked out over the mountains encircling us in a silent panorama, one lofty peak dwarfed by the next. It was incredible.

Breathing easy

On day seven after breakfast in the cosy teahouse kitchen – Tibetan coffee and tsampa porridge with the resident lama – we set off back down the trail. You can make it all the way back down to Syrabru Besi in one day, but we weren’t in a hurry. We stopped at a teahouse on the river, at around 2790 meters and breathed easy next to the icy rushing water.

We walked back into Syrabru Besi the next afternoon in the first rain we’d seen since Darjeeling. In a serendipitous moment we stumbled upon a little slice of paradise – a tidy guesthouse with warm rooms and cold beer. And, it was right next to the bus station for the steep ride back down to Kathmandu the following day.

Solo-trekking in the Himalayas: Oyv got a nasty blister and that was the worst of it. Although I did miss the hair straightener a bit.

Read More

For more of our adventures (and misadventures) as we travel from Cameroon to Japan, check out the rest of my stories from the road.

Thinking about taking this solo trek on too? Read our post for advice: Trekking Langtang valley without a guide: itinerary and planning.

Or if you’re still in India and planning to travel to Nepal by road: How to cross the Sonauli border between India and Nepal.

This Post Has 2 Comments

Thanks for visiting Nepal and Langtang Himalaya. Everest, Annapurna, Kanchenjunga, and many more Nepal himalayas are ready to welcome you to Nepal.

This post offers an engaging and immersive narrative of traveling through India and Nepal, highlighting cultural experiences, personal anecdotes, and unique encounters. However, it could delve deeper into broader issues like road safety, women’s safety at festivals, and the environmental impact of tourism.