We finally left Africa on a late night flight from Asmara, moving on to Turkey and the next leg of this trip – heading east from Istanbul. But first, we spent a few days just enjoying this magnificent city whose citizens seem to take an obsessive approach to both cats and breakfast. Gotta love a place that specializes in two of my favorite things.

Istanbul’s famous for its feline rulers, who graciously share the space with the humans who feed them and obediently build little houses for them.

Almost every cafe, bar, and restaurant has at least one or two cats acting like they own the place, to the point where the best seats are taken (under the heat lamp, for example, it’s getting cold now).

I for one, wouldn’t dare object.

As for breakfast – countless cafes and restaurants serve up a traditional kahvalti (a sort of morning mezze to pick and choose from).

Lingering over the meal each day – preferably with a cat in my lap – is my favorite thing to do here.

I felt like I could just stay in Istanbul, breakfasting and hanging out with cats, but then Oyv and I would probably have to get divorced. And besides, it was time to get this show on the road. We were bound for Iraqi Kurdistan: an autonomous region in northern Iraq. It’s a part of the unofficial Kurdish homeland which also spreads into bordering areas of Iran, Syria, and Turkey.

Still, we weren’t in any rush to get there. We had time to kill and a bit of Turkey to cross. After all, Turkey is not just about cats and breakfast. There’s also baklava.

And hair transplants. Anyone transiting through Istanbul’s airports will see flocks of men with fragile bright red scalps recently sewn with relocated hair and covered by bandannas advertising the clinic they went to. And now, based on our recent experience, I’m going to add mausoleums to the list. On our meandering way to Iraqi Kurdistan, we didn’t realize it at the time but we were embarking on a tour of famous tombs.

Obviously, there’s Ephesus

Ephesus was an important center for early Christians from around AD 50, though it’s much older than that. The Apostle Paul spent time here while he was writing 1 Corinthians. Not everyone appreciated Paul’s letters – he wrote his epistle to the Ephesians from prison in Rome later on.

Ephesus is still very atmospherically intact.

The number one attraction has to be the Library of Celsus, built around 125 AD to hold nearly 12,000 scrolls. A retired governor in the Roman Empire, Celsus paid for the library’s collection himself on the understanding that he’d be buried beneath it.

The city is also home to one of the biggest amphitheatres in the ancient world. Up to 24,000 citizens who weren’t otherwise occupied with all the scrolls at the library could watch gladiators fight to the death instead.

Tombs are popular with pilgrims, too

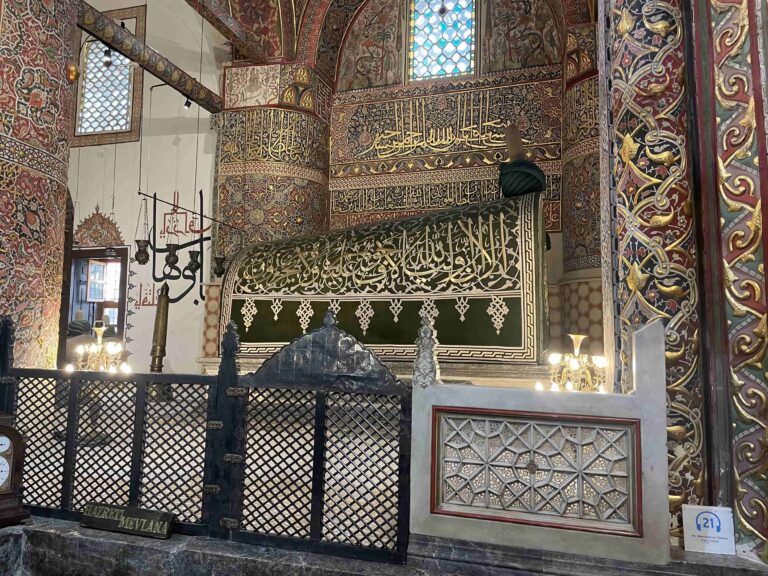

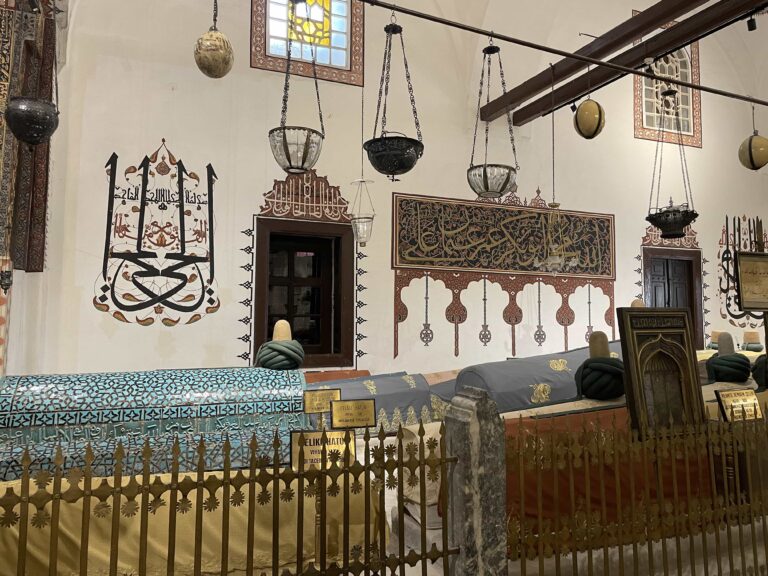

One of Turkey’s most conservative cities today, Konya is built around a famous mausoleum complex.

The entombed corpse in this case was a Persian poet, philosopher, and teacher named Rumi who lived in Konya from 1207-1273. Known as Mevlana, ‘the master’, he taught a mystical interpretation of Islam called Sufism, based on purification, rituals, spirituality, and asceticism. Adherents to the Sufi order are known in the West as ‘whirling dervishes’.

Sufism is sometimes a topic of controversy: in fact we’d been warned off visiting Konya altogether by a waiter (at breakfast, of course) who informed us that ‘Bad people live there’. But the waiter’s opinion hasn’t stopped seemingly all the old people in Turkey from visiting Konya at once, not to mention the elderly pilgrims from abroad who overwhelm the mausoleum complex.

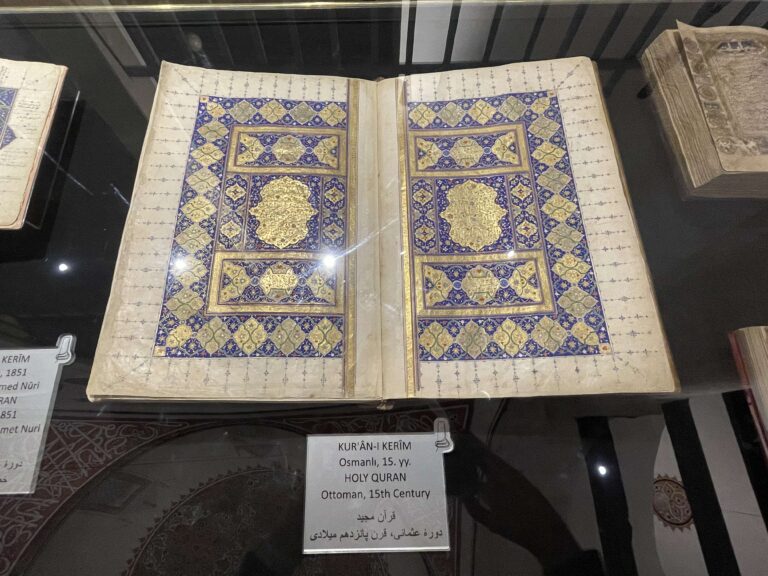

The mausoleum also contains the coffins of other dervishes and a collection of ancient and beautiful Korans.

Obscure kingdoms

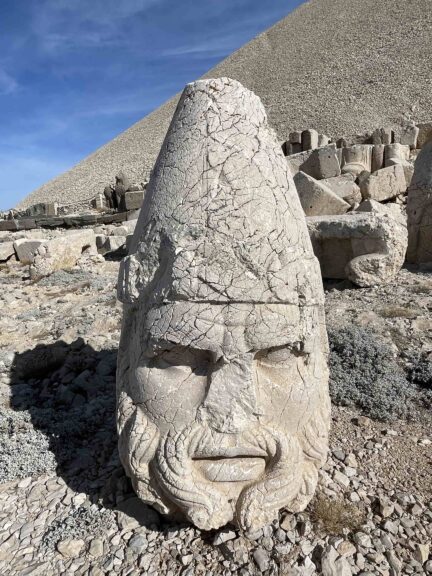

Maybe you’ve heard of the Kingdom of Commagene, maybe not. It doesn’t really matter – they didn’t leave much behind when they were swallowed up by Rome. But what they did leave behind is mainly at the top of Mount Nemrut, one of the highest peaks around. King Antiochus didn’t stop at digging out his tomb on the summit in 62 AD. No, he surrounded his final resting place with huge 8-9 metre high statues of himself, lions, eagles, and a few Greek and Persian gods he no doubt considered himself in league with.

The statues’ heads are long since detached and scattered around like huge broken toys.

It’s thought that the tomb itself, a conical hill, was deliberately covered in loose stones to make it harder for grave robbers to dig in. It’s true that no one has ever opened the tomb to check if Antiochus is actually inside, but they are pretty certain he is.

And it’s not just tombs that stand the test of time. There’s a Roman bridge nearby, built in 190 AD. This feat of ancient Roman engineering was still in use for regular traffic until the early 2000s.

The main event

Finally, we boarded a bus that would take us out of Turkey altogether and into Iraqi Kurdistan. We drove past kilometers of fencing, watchtowers, and checkpoints, and processed immigration. Although Iraqi Kurdistan is technically in Iraq, it is autonomously governed and requires a separate visa and all the other bureaucracy that comes with a border crossing (around here, anyway).

It was dark when we arrived in Duhok, a city whose existence we were only previously aware of because there is a hairdresser’s on our street at home named after it. Duhok Hairdresser is constantly filled with men who aren’t getting their hair cut, but simply seem to be drinking tea and passing the time of day. They obviously copied this concept directly from Duhok because the entire city was filled with men drinking tea in the bazaars, at street stalls, and in shisha lounges.

Having just about exhausted ourselves lately on mausoleums and the whims of those who build them, we took a break and immersed ourselves in another major feature of the region: the bazaars.

We wandered into teahouses and drank glass after glass of sugary chai and arabic coffee.

We ate enormous meals meant for one that covered the entire table top.

After dinner, we got into the habit of popping by a sweet shop to browse to rows of candy and pastries. And by ‘browse’ I actually mean, get fed our dessert in samples, and possibly hot chocolate.

Revitalized and ready to sightsee in the land of the living for a change, we organized a daytrip to Lalish and some surrounding villages. Abdul the taxi driver was on a mission: oncoming traffic did not faze him and he drove fast and furiously down the middle of the road, occasionally muttering into Google Translate and then pointing his phone at one of us. He was considerably more cheerful once we agreed to him smoking in the car. Smoking indoors everywhere and all the time, is still very much a thing here.

Abdul was silent for much of the drive from Duhok, until we reached the first checkpoint and handed our passports out the window to the soldier manning it. The soldier looked briefly at our documents and waved us through. We’d barely passed the checkpoint when Abdul spat at the window and rolled it up. Via Google Translate he informed us that the soldier who’d asked for the passports couldn’t read them anyway, and was therefore a donkey – a pretty major insult around here. Abdul seemed personally offended, and we drove on in an awkward silence.

Checkpoints are a regular feature on the roads in Iraqi Kurdistan, and we passed through many during our travels. We very rarely had to get out of the car and talk to the soldiers. In most cases they just wanted to know where we were from, and confirm that neither of us is actually a journalist. But there’s an extra rule at the checkpoint right outside Lalish – we had to take off our shoes, and leave them there. Abdul was ok with this. Footwear’s not allowed in Lalish – not even on cold and rainy days in November.

Lalish is a Yazidi temple built around – you guessed it – the founder’s tomb. There are less than a million Yazidis worldwide, and each one is expected to make a pilgrimmage to Lalish at least once in their lifetime. Just sixty kilometers north of Mosul, only about twenty-five people actually live in Lalish but during ISIL’s relentless persecution of this peaceful religious minority in the 2010s, many others fled here for refuge.

It’s around this time that we started delving into more recent history.

On another daytrip from Duhok, we circled a roundabout featuring a bronze bust of a mustachioed man in the centre and I asked our current taxi driver who he was.

The driver’s response was brief. The only words I picked up were ‘Generale’ and ‘Saddam Hussein’, accompanied by the driver gripping his own throat and squeezing it. We took this to mean the bust honoured a key player in the infamous dictator’s capture and execution – at any rate, it wasn’t a bust of Saddam Hussein himself. As we climbed out of the car in front of yet another kebab restaurant, I asked the driver where to find a ride back later. He pointed over his shoulder towards the roundabout and grabbed and squeezed his throat again.

Saddam Hussein’s government relentlessly persecuted the Kurdish people (amongst others) particularly at the end of the Iran-Iraq war in the late 1980s.

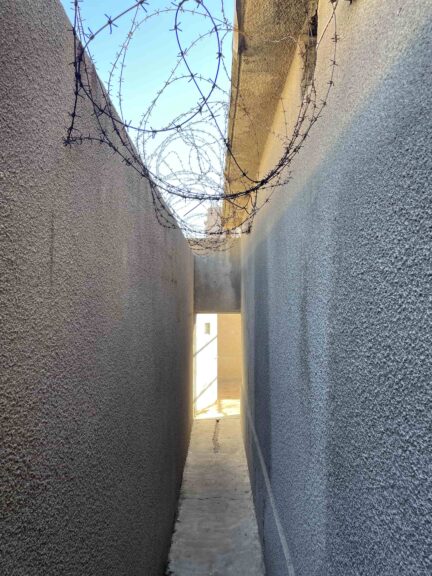

From 1979 to 1991, the Iraqi intelligence agency was headquartered in Sulaymaniyah, the city we moved on to next. From the street this notorious prison looks like any other building (if you look past the bulletholes sprayed across the outer walls), but up until the early 1990s it held Kurdish nationalists, students, and other dissidents. It’s now a very disturbing museum, documenting the human rights abuses under Saddam’s rule. There’s a row of rusted Iraqi tanks in the courtyard, and exhibits of artifacts collected from prisoners.

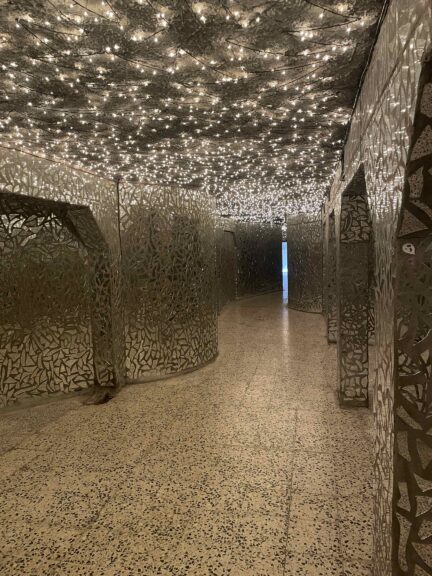

To enter the museum, you walk through a hall of broken mirrors where 182,000 shards of glass commemorate each Kurd killed during the time of persecution and genocide.

In 1988 Iraqi planes dropped chemical weapons on the nearby town of Halabja. At least 5,000 civilians died instantly and an estimated further 7,000 were injured or suffered long-term illness. There’s a monument on the edge of town commemorating the victims and testifying to the Kurdish people’s resilience in the face of such atrocity.

But that’s not all

We knew about these terrible things up front. But there were so many positive surprises too, in Iraqi Kurdistan.

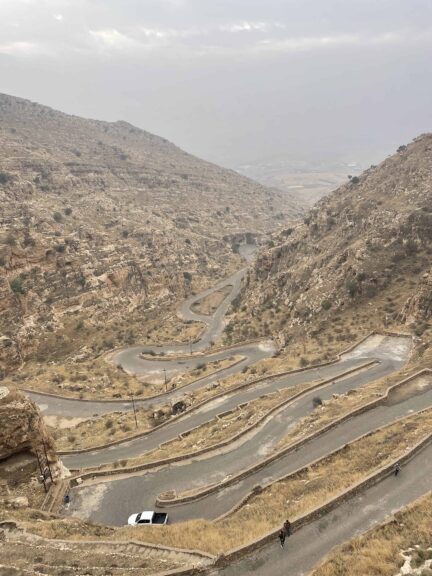

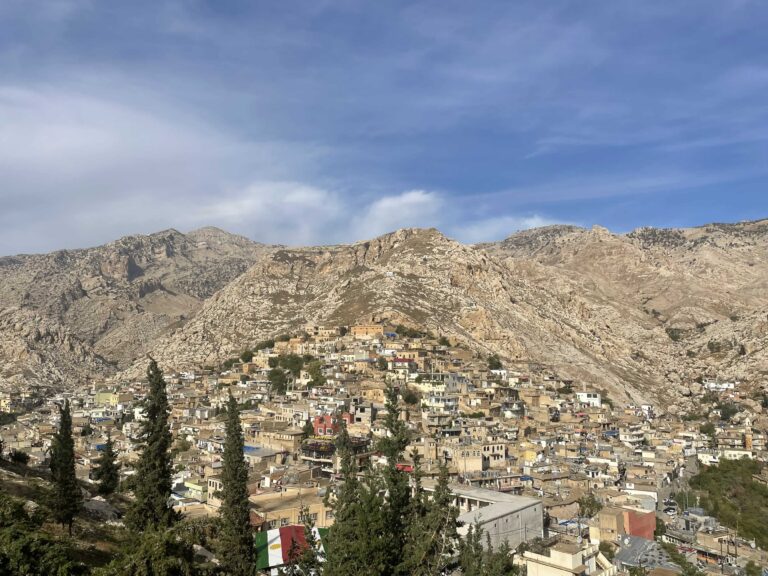

Steep rocky mountain roads lead to little villages with big views.

There’s religious diversity – we visited Christian monasteries and churches too.

It didn’t feel overly conservative either – we saw lots of young men and women mingling together and few women covering up. The cities we visited are peppered with trendy cafes alongside the more traditional shisha bars. There’s even an English pub in Erbil. We know because we spent a rainy afternoon daydrinking there.

And you can bet we scoped out some great breakfasts, too.

Coming right up: it was around this time that we both developed Covid. Not a major concern in most places anymore, but Turkmenistan is not like most places…

Read More

For more of our adventures (and misadventures) as we travel from Cameroon to Japan, check out the rest of my stories from the road.

This Post Has 2 Comments

Keep writing…it’s so interesting!

Will do!