At the Afghan Embassy in Tashkent, amongst other semi-helpful pearls of wisdom we’d gleaned from the consular officer was a warning that we shouldn’t cross the Torkham border from Afghanistan to Pakistan. There’s a refugee crisis going on. Pakistan is throwing out thousands of people with ties to Afghanistan – even people who’ve lived in Pakistan most of their lives – apparently because of the threat posed by the Pakistan Taliban. It doesn’t have much to do with civilians but nevertheless they’re being sent in droves across Torkham border into a country they may or may not have ever called home. Queues at the border have been out of control with people stuck for days in makeshift camps. To make things worse there’s been fighting between the armies on either side recently, resulting in random border closures. Not just because of actual violence, but also due to perceived insults, like the correct placement of a Welcome sign. Getting stuck on a border between two very unfriendly neighbors did not sound like a good time to us.

Once we got pretty close to the infamous border crossing, we asked around about the current situation. As usual when we inquired in Afghanistan about safety, the answer was that there would be ‘no problem’ for us. Anyway, we had to get to Pakistan and we’re big fans of overlanding, so that’s what we did. And as it turned out, all the problems were waiting for us on the other side of the border.

We drove to Torkham on a sunny day through little villages and leafy orange groves. The road was punctuated by sandbagged fortifications, watchtowers, and the rusted leavings of the Americans.

A lively dispute about the Taliban broke out in our share-taxi. In case you’re wondering: our seatmate in the back loves them, but he was shouted down by the driver and front seat passenger. Our seatmate turned to Oyv. ‘Do you love the Taliban?’ he wanted to know. That was awkward. We emphatically do not. We also didn’t want to offend either the frontseat or the backseat. But there was no need to worry. The Taliban-fan took a break from the conversation to open Facebook and send Oyv a friend request. The driver stopped the car, jumped out, and bought us all some fake Red Bull to cool down.

In Torkham we changed the last of our Afghanis to Rupees.

Then we walked a few hundred meters to where the series of fences and gates and soldiers began. The border is hectic, that’s true. In addition to heaving crowds of refugees there’s also the import/export that goes on at every crossing, with locals transporting enormous amounts of stuff back and forth. I watched some men pull a body on a stretcher out of the back of a taxi. That was new one.

Exiting Afghanistan was straightforward but as soon as we’d been stamped out and started into no-man’s land, the chaos we’d heard about ensued. Following local advice, we didn’t join any of the long queues but just kept moving ahead through a fenced and tarp-covered passageway. Somebody had been alerted to our presence; a Pakistani immigration officer came for us. We passed guards who shouted and occasionally slapped people. As foreigners who clearly aren’t seeking refuge on either side, we were kind of just pushed through the border in a surge.

But not without getting a polio vaccine – twice. International Yellow Vax cards mean nothing here.

The Pakistani officer sat us down on a bench in the midst of all these people and baggage, mud and barbed wire. He asked us questions, examined our visas, and fingerprinted and photographed us several times before escorting us onwards.

I looked at the Pakistan stamp in my passport, and I’m not gonna lie: I breathed a tiny sigh of relief. Afghanistan is the kind of place where things can change quickly and you’re safe until you aren’t. But we’ve been to Pakistan before. It felt familiar and comfortable.

But not too comfortable

It seems I was too quick to let my guard down. Literally. The immigration officer reappeared and informed us that it wasn’t safe for us to travel alone to Peshawar. As foreigners we wouldn’t be allowed to spend the night there, either. This was quite a change from the constant reassurances regarding our safety, from literally everyone in Afghanistan.

And so we found ourselves in the back of another taxi, this time riding through Khyber Pass with an armed guard in the front seat.

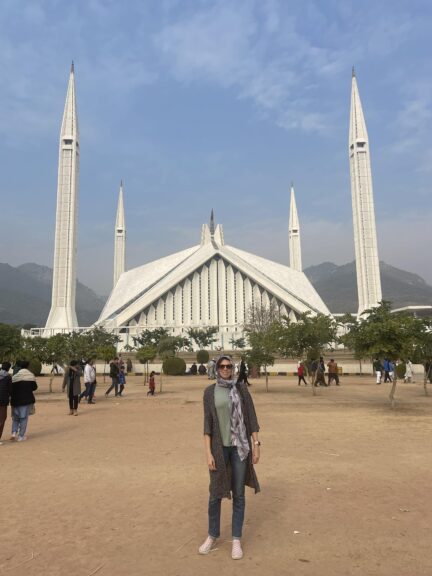

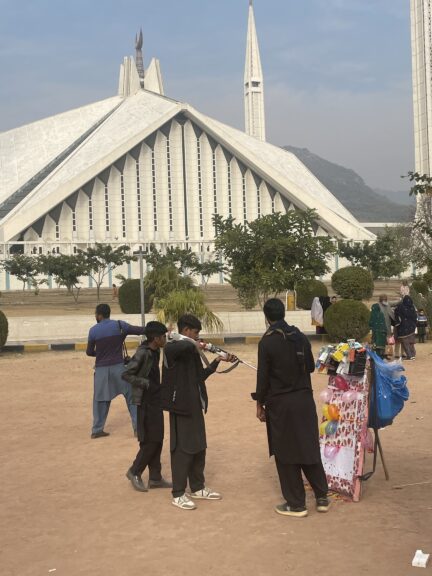

Although the police didn’t want us in Peshawar they were fine with us taking a bus out of it so we carried on alone to Islamabad. Islamabad is a place where you can literally breathe a sigh of relief and not just because it’s the safest city in the country. The capital is spacious and airy, full of wide tree-lined streets and green spaces. Now, finally, I could let my hair down – I mean, I could take off my headscarf – and enjoy. Enjoy coffee, that is, still no wine here.

We enjoyed Islamabad so much we stayed longer than we meant to. Alright: we discovered The English Tea House down the road from us. They serve delicious breakfasts in a sunny country-estate-library type setting. We deserved it after the greasy fried eggs and bread with tea we’d eaten every morning in Afghanistan.

Entertaining foreigners in the City of Saints

Even Oyv and I can’t linger over breakfast forever, so we decided to go to Multan, a city in southern Punjab province. In the 11th and 12th centuries Multan was veritably bursting with Sufi mystics, and that means that today there are a significant number of dead Sufis enshrined in and around the city. So many that Multan is also called the ‘City of Saints’ and Dar al-Aman, or ‘Abode of Peace’. Sounds chill, no? Well…no.

We already knew Multan doesn’t go easy on travelers. A lot of hotel listings had prominent notices stating that they won’t entertain foreigners (or worse, unmarried couples). We’d heard it was possible the police might even put us right back on the bus to wherever we came from. Basically the City of Saints doesn’t see a ton of foreign visitors. But when we got off the bus there and stood on the side of the road waiting for a taxi, nobody looked askance at us. Ok, every person driving by looked at us, but not in an askance way.

At check in the hotel receptionist pushed a laminated sheet across the counter. It was a list of rules the hotel expected us to abide by such as being married, and things they weren’t responsible for, including any deaths on the premises. The receptionist tapped rule number five briskly. ‘Foreigners are not allowed to leave the hotel without the police’. He tapped it once again and made us sign a form.

And so we learned that foreigners can visit Multan all they want: assuming they find a hotel which will entertain them, possibly get married first, and don’t mind visiting the Abode of Peace with armed guards and a police escort.

Independent exploration was out, so we had to arrange a car and driver to take us around. The next morning we went downstairs and were greeted by a team of police officers and our driver, Bilal. ‘I’m sorry for my English, sir’ he said to Oyv. ‘In advance, I am sorry for everything and for anything in the future, too’, he went on. Bilal’s English was actually pretty good, and the main thing was that he wasn’t at all disturbed about driving his car in a convoy with the police.

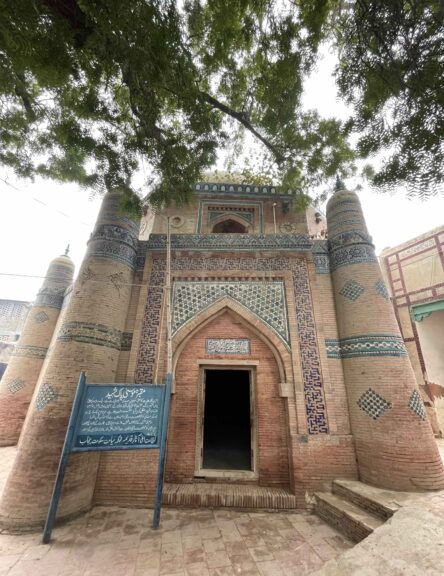

We drove to neighboring Uch Sharif. It means Noble City, and seventeen Sufi shrines – not to mention around 1400 graves – surround the modern town. Uplifting, I know. Maybe that’s what Bilal was apologizing for.

Bilal doesn’t tend to drive a lot of foreigners, since foreigners don’t tend to come to Multan. That must be why he wanted to know how Pakistan compared to every single country we’ve ever been to, and asked us to rate it on a scale of one to ten. Apparently he liked our answer because I saw a tight little grin on his face in the rearview mirror. His next question threw us for a loop though: ‘How old am I looking?’ We’d thought he was about forty. It was his demeanor as he shepherded us around, checking if we were hungry, and constantly reassuring us of our total safety and then immediately warning us about the dangers presented by ‘uneducated people’ in small villages. But no, Bilal was just managerial beyond his twenty-eight years. Either way, he was in charge now. We were helpless in the face of his friendly bossiness so we hired him to take us around the next day too.

‘Am I looking married?’ Bilal asked us as we drove towards the Thar desert to check out the crumbling ruins of a ninth century fort (and the royal tombs across from it). Given his ripe old age of twenty-eight we correctly answered yes. In fact he was a newlywed, married just two months earlier. ‘My wife is wanting to speak with you’ Bilal said, and handed his phone to me. But she couldn’t speak English so it was a pretty one-sided conversation. We settled on taking group selfies – the three of us and the police officer currently riding in the front passenger seat – instead.

Sufi mystics and modern zealots

The plan after Multan was to continue south to Sukker, in Sindh province. Our orchestrated departure involved breakfasting with police parked outside the restaurant, who then escorted us to the bus station and called our taxi driver three times during the short trip. They seemed keen to get rid of us. We boarded our bus, free at last. For the moment, anyway.

One of the first areas of the Indian sub-continent to fall under Islamic rule, Sindh is sometimes called Bab-ul Islam or the ‘Gateway of Islam’. It’s a region of mystics, deeply influenced by Sufism, and like Multan it was once home to an enormous number of saints and mystics preaching peace and religious tolerance. Today it’s home to incredibly zealous police who make difficult for foreigners to visit.

Arriving at a guesthouse in Sukker we breathed a tiny sigh of relief. Despite the guesthouse’s many shortcomings – it was dirty, the bathroom smelled awful, and there was no hot water, – there was also no list of rules for us to sign. But as we got out our sleep-sheets and distastefully pushed the blanket off the bed, there was a knock at the door. Our host informed us that no matter where we went out of town tomorrow, security would be accompanying us.

Our main interest was in yet another Sufi Shrine, in this case the Shrine of Sachal Sarmast. Known as the ‘intoxicated man of god and truth’ – extravagant nicknames are just rife around here – he was an 18th century Sufi mystic and ascetic, spreading a message of divine love through his poetry.

‘Where crowds are, there I am not’ Sachal Sarmast famously said. That didn’t really work out for him. He died in 1829 and every year crowds in the thousands gather at his resting place on the anniversary of his death.

We paced quietly around the shrine. To us it’s just another elaborately beautiful tomb, but to his followers it’s a significant place of pilgrimage – unless two foreigners happen to be there in which case all hell breaks loose (only in a phone-waving, selfie-requesting sort of way).

So what’s all the fuss about? We still aren’t sure.

Back in Sukker we went out to explore the city. The threat to our safety seemed pretty low-key. Everybody smiled widely at us, welcomed us, and at most wanted photos and a chat.

But even though we were free of the police in town, our host at the guesthouse seemed to feel responsible for us. Possibly he was. He called us repeatedly like a concerned dad (he was at least twenty-eight years old), asking when we’d be back and trying to coerce us into ordering takeaway and eating dinner safely locked in our dingy room.

As far as we know, the constant policing isn’t for our own safety as much as it is because of sensitive army activity, in Multan at least. Oyv suggested it was a weird side effect of the famous Pakistani hospitality – you know, making sure foreign guests don’t die. Whenever we asked why we needed it, we heard the same reason: it wasn’t safe for us to travel alone because of the many ‘uneducated people’ apparently residing in the villages. It’s not like Pakistan prioritizes public education, so maybe it’s not surprising there are so many supposedly dangerous uneducated people. Whatever the reason for it – it felt unnecessary to us both – all the security measures had us at our wits’ ends.

So we boarded our next bus – heading north – with a tiny sigh of relief.

Read More

For more of our adventures (and misadventures) as we travel from Cameroon to Japan, check out the rest of my stories from the road.

Or have a look at stories from our previous visits to Pakistan (no guards!).

This Post Has 4 Comments

Great post- again! I hope you tried some Multani Sohan Halva, one of my personal favourites.

Thanks:) And no, I didn’t try it…regretting it now, lol

Another good one! I had a similar issue on a recent trip to Bangladesh, where the police and hotel workers and others wanted to keep tabs on me, or protect me. No one in Bangladesh said anything about danger, or uneducated villagers, but I’m pretty sure the idea was that I was sure to be bothered by locals who were not sophisticated and who were likely to embarrass themselves and show the country in a bad light, so it would be better that I didn’t meet any of them. I’ve had the same now and then in India. There’s also the general notion that foreigners (Westerners) are wealthy and therefore delicate and unused to hardship and wouldn’t know how to function in countries like theirs that are hectic and dirty and uncomfortable.

Yes, I think so too. But it’s a persistent thing in certain areas of Pakistan, and a little different as far as the police go. It depends on what is going on in any particular region at the time – we’ve traveled to and stayed in Peshawar on a previous trip without hardly a glance from the police other than a quick checkpoint here and there. The last time I was in Bangladesh, I had a lot of people in general trying to protect me from all sorts of ‘dangers’ (I think especially because I was alone), but never had security actually forced on me. We’re on our way there now, hoping that hasn’t changed…